Waterlust and the Watson Fellowship

Imagine receiving funds to spend your post-graduate year studying fly-fishing in Latin America, lunar festivals in Southeast Asia, or fiddling traditions in Europe — an entire year to travel anywhere (outside the United States) investigating the evolution of snowboarding, mysteries of the tango, modern piercing culture, diversity of tropical frogs, or the emergence of women taxi drivers. These topics have all been researched by Watson Fellows, recipients of the Thomas J. Watson Foundation’s fellowship that began in 1968 to give "college graduates of unusual promise the freedom to engage in a year of independent study and travel abroad following their graduation." The fellowship is now awarded annually to up to 60 students nominated by 50 member private colleges and universities in the U.S. Vassar joined this group in 1991, sending its first alum to the Watson ranks in 1992. The Watson Fellowship has become a popular option for Vassar students yearning to explore the world. Approximately 40 seniors apply for the four nomination slots Vassar is asked to submit to the Watson Foundation each year, according to Susan Davis, director of the Office for Fellowships, Graduate Studies, and Pre-Professional Advising. "I think the goals of the Watson Foundation match closely the aspirations and talents of many Vassar students," Davis said. "Vassar students ‘get’ the Watson. It’s a vehicle to make a dream-year a reality." At least one Vassar graduate has been chosen for the fellowship each year since Vassar joined; in 1995, Vassar was the only college with three Watson winners. Davis reported that all Vassar Watson Fellows’ experiences have been "life-changing or affirming. The Watson can turn everything upside down or confirm long-held aspirations." Here, ten Vassar Watson Fellows tell their stories.

"The Fellowship Program provides fellows an opportunity for a focused and disciplined wanderjahr of their own devising — a period in which they can have some surcease from the lockstep of prescribed educational and career patterns in order to explore with thoroughness a particular interest," reads the Watson brochure. "During their year abroad, fellows have an unusual, sustained, and demanding opportunity to take stock of themselves, to test their aspirations and abilities, to view their lives and American society in greater perspective, and, concomitantly, to develop a more informed sense of international concern." Fellows are not permitted to return to the U.S. during their Watson year, nor are they allowed to formally study at foreign institutions. They are encouraged to visit countries in which they have never before spent a significant amount of time, and their projects should reflect interest in, and commitment to, specific concerns.

Amy Vogelaar ‘92

Watson Project

Working with midwifery organizations to learn more about women-centered childbirth practices and health care systems

Watson Locations

The Netherlands, Sweden, Honduras, and Guatemala

Why?

Vogelaar stumbled across her interest in midwifery while searching for a paper topic for her sociology class (Sex, Gender, and Society). The women’s studies major became "completely fired up about it — they say midwifery is a calling!" Vogelaar, Vassar’s first Watson Fellow, says the moment she heard about the fellowship, she knew it was a perfect way to pursue her interests.

Watson Challenges

"Different cultures reacted very differently to me. The Dutch have a network of midwives who are very welcoming, and they were wonderful teachers. But the Swedish were much more formal and private, somewhat foiling my project there. I became extremely frustrated, but the Watson Foundation encouraged me to experience the culture rather than worrying about the particulars of the project itself. In Central America, it was very challenging to even find the midwives because they were working in rural communities without phones. But the Watson is about coping in the world, going with the flow, and learning about life… I most cherish the times that were difficult. If I got through that, I can get through anything."

What Now?

Upon return from her Watson year, Vogelaar could not stand still. "I never traveled before the Watson, but I’ve been traveling constantly ever since." She bought a car and drove across the U.S. before settling down to work as a sex educator for Planned Parenthood. This winter, she will complete her program at the Seattle Midwifery School. Next stop Bahrain, where she hopes to someday start a home-birth business.

Karin Betts ’93

Watson Project

Titled "Intentional Communities: Cooperative Living and Communal Responsibility," Betts’ project sent her to intentional communities. She worked in the communities to make herself a member rather than a visitor.

Watson Locations

Israel, India, Denmark, and Scotland

Why?

Betts, an international studies major, worked at an educational summer program before her senior year at Vassar. Global Youth Village was conceived and run out of a community of Americans with similar spiritual and moral commitments. "I was intrigued by the sponsoring community," she says. "They were able to achieve much more as a community than they would have as loosely grouped individuals." Her Watson project was intended to allow her to more deeply examine such communities around the world.

Comparing Communities

During her seven months in Israel, Betts worked at two very different kibbutzim. At the older kibbutz, Regavim, she worked alternately in their plastics factory, ostrich farm, and kitchens. At Yahel, a Reform Judaism kibbutz in the Negev Desert, Betts worked in the community’s kosher dining hall. In southern India, she lived and worked at a community-based training center for lower caste and "untouchable" people, where she edited their English-language materials. After expanding her project to visit several spiritual communities in India ("Something about India spins the mind and soul in spiritual circles"), she headed to Western Europe to work with a folk high school in Denmark and a new-age community in Scotland. Betts says the only community she truly felt part of was Kibbutz Yahel, where a resident Vassar alumna warmly took her in.

What Now?

"My experiences over the course of my Watson year made the notion of a traditional nine-to-five job unacceptable to me. They gave me an appreciation for the rewards of physical labor, and for the pace of slower, more purposeful cultures. The Watson opened up the world to me in such multidimensional ways that I want always to live somehow in the midst of its chaos and diversity." Betts is now designing and leading educational tours in Bali, Java, Komodo National Park, and Borneo, Indonesia.

Eric McGlinchey ’95

Watson Project

Exploring the economic transition and trade routes of former Soviet Central Asia

Watson Locations

Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Estonia, Japan, and China

Why?

McGlinchey first became interested in the topic when he traveled the Trans Siberian Railroad during his junior year abroad in Yaroslavl, Russia. "The train to China was a living stereoscope: Looking out the window at 54 kilometers per hour, things change slowly. Russia bleeds into Asia; geography and facial features change almost imperceptibly. I made fast friends of my travel companions — Russian, Caucasian, Mongolian, and Chinese shuttle traders plying their goods between Moscow and Beijing. I returned from my first Trans Siberian trip eager to travel other trade routes among the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union, and the Watson Foundation kindly set me back on the rails."

Finding his own route

Although he would come to spend more than three months on trains during his Watson year, McGlinchey set up a home base in Yaroslavl. His first destination was the immense Tien Shan Mountains in Kyrgyzstan. There he felt lost without any sort of methodological plan to analyze the culture of the shuttle traders and knowing nothing of the region’s glacier travel, technical climbing, or mountaineering. He forged on to the historic cities of the silk route: Osh, Kyrgyzstan, and Bukhara and Samarkand, Uzbekistan. For his next journey, McGlinchey met up with Vassar friends to travel from Tartu, Estonia, to Kobe, Japan. He then made a solo return to Beijing to conduct interviews with members of the Russian training community before training north to Urmqi, China, a hub for the Pakistani-Chinese-Russian trade. For the final third of his Watson year, McGlinchey stayed off the rails and devoted his attention to the Moscow bazaars, "the hub of all post-Soviet trade."

What now?

"The Watson year introduced me to three continuing loves: field research, mountaineering, and, of course, Central Asia. I’ve been fortunate that I can combine all three." In 1999 McGlinchey returned to Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan as an IREX (International Research and Exchanges) research fellow, spending weekdays in archives and weekends in the mountains. He is now in his final year of his dissertation at Princeton. "When not chained to my desk, I’m roped up with my climbing partner on the Shawangunk cliffs just across the river from Vassar."

Jessica Lawrence ’95

Watson Project

Observing the social and political dynamics of conservation efforts and their impacts on small communities in forest regions

Watson Locations

Belize, Guatemala, and Indonesia

Watson Challenges

Lawrence said that it was incredibly challenging to be on her own, without any structure. "I was rootless, trying to find meaning." She volunteered at organizations in each location, mainly shadowing and observing, but she felt isolated much of the time, especially since she is not fluent in Spanish or Indonesian. She also felt as if she could potentially be in danger, as a woman, and was thankful she had taken self-defense classes at Vassar, which helped her keep her sense of danger realistic. But in the end, Lawrence said, it was the lack of structure that made her experience worthwhile. "It’s liberating, and incredibly wonderful that the Watson supports you to be eccentric and unique, without academic guidelines."

Favorite Watson Experience

"Living with local families in the forest regions and seeing the dynamics of corruption woke me up to the reality of what happens at ground level. Plus, since I was independent of any institution and not there to fund, people shared their despair and hopelessness, without promoting their projects. My being unattached allowed people to trust me with their stories."

What Now?

After her year living among forests, Lawrence went on to study them more formally at the Yale School of Forestry. She now works for the Rainforest Action Network in San Francisco.

Oren Rosenberg ‘96

Watson Project

Studying the ecology and evolution of infectious diseases, such as malaria, AIDS, and rabies. Rosenberg collected data for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s field stations and completed a veterinary project in the Serengeti National Park.

"You can't just sit in your research laboratory and forget about the rest of the planet." —Oren

Watson Locations

Guatemala, Kenya, and Tanzania

Why?

"I was a biology major at Vassar. In my junior year I took John Long’s class on evolution and got really interested in the evolution of infectious diseases — how the populations of organisms that cause these diseases are altered by human behavior and environmental changes."

Favorite Watson Experience

His time in the Serengeti, surveying the domestic dog population in the area just outside the park for rabies and canine distemper virus. "In years past, these diseases, after being transmitted from domestic animals, had been responsible for the deaths of many carnivores living inside the park. For example, in 1994, one third of the lions living in the Serengeti were killed by canine distemper virus."

What Now?

Rosenberg is currently in his third year of the M.D./Ph.D. program at Yale University School of Medicine. He does not think he would be on this track if he hadn’t done the Watson. "It made me realize that whatever you do has a context — you can’t just sit in your research laboratory and forget about the rest of the planet."

Cheryl Scheffler ’98

Watson Project

Studying alcohol and drug addiction: the laws surrounding them, different forms of treatment, and their impact on societies

Watson Locations

England, Switzerland, Scotland, and the Netherlands

Why?

Alcohol and drug addiction have had a big impact on Scheffler’s life, as it does for many. She wanted to examine other nations’ models for handling addiction. She found that substance abuse looks the same in every country ("It’s ugly and it kills"), but that nations’ responses to addiction can be very different. "In Amsterdam, those with substance abuse are treated with compassion and tolerance; they are included, not shut out," she observed.

Watson Challenges

"My receipt of the Watson was a bit unusual. I am, and was in 1998 when I got the Watson, an older student. I began my higher education at Vassar in my early 40s, so I received the Watson in my mid-40s. [It was life-changing] in every way. I no longer had any of my roles to fulfill: mother, grandmother, daughter, girlfriend, etc. I knew no one. I was an older adult traveling on a youth’s budget. I had never been out of the country. I learned to shift my way of thinking about my topic. The American way is not the only way, but that took living in [a different] culture to experience why and how another way might work within another culture."

What Now?

Scheffler was accepted to a graduate social work program at Smith, but deferred for the Watson. When she returned, Scheffler was unsure whether she wanted to study the policy that she no longer agreed with. But she went to Smith, and is now working at the St. Frances Counseling Center in Dutchess County, where she works with people with co-occurring disorders (substance abuse and chronic mental illness). "The Watson gave me compassion and tolerance that I didn’t have from learning and training in this country," she said.

Emily Porter ’99

Watson Project

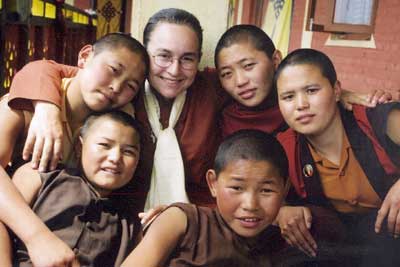

Exploring transitions in Buddhist nun communities by living in, and among, diverse nunneries across Asia

Watson Locations

Nepal, India, China, Thailand, Taiwan, and Mongolia

Why?

A philosophy major, Porter became interested in how people lived philosophies while she studied in China during her junior year. She spent weekends visiting temples, monasteries, and nunneries; eventually, complicated questions brewed surrounding the seemingly limited situations of women practitioners. "I was confused as to why, within a philosophy that views things such as gender as having only a conventional, not a solid or ultimate reality, women would be denied certain opportunities to practice just because they were women." She decided to use her Watson year to continue seeking answers to these questions, by integrating herself in these communities as much as possible. During her year she attended His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings and helped set up the sixth International Conference of Buddhist Women.

From Vassar to Watson

"A Vassar education and a Watson Fellowship offer similar settings in the sense that both refrain from placing a lot of external requirements, rules, and guidelines for how to proceed through the space of their experience… The Watson offers a sacred openness, a spacious workshop for the mind to explore its own limitations and abilities. [Meditation Master] Chögyam Trungpa [Rinpoche] once described meditation as giving a wide open, luscious field to a restless cow. The Watson could be similarly described. It is within such a spacious opportunity that one has the chance to see the self-imposed limits of one’s own imagination."

What now?

Porter is currently working in Taiwan, saving money so that she can always have the ability to take time off for exploring. Her article, "Nuns in Mongolia," was published in the March 2001 issue of Mandala magazine. (Find the complete article in the Extras section.)

Margot Stiles ’99

Watson Project

Examining the tradition, ecology, and community of fisheries by looking at the ways in which people other than scientists and environmentalists ("the 90 percent of the population that isn’t interested in the environment") impact conservation efforts

Watson Locations

New Zealand, Chile, and South Africa

Why?

Stiles first studied a system of fishing territories during her junior year abroad in Chile. The biology major started thinking on a local level, wondering in what ways members of fishing communities become directly involved in conservation. For her Watson year, she returned to Chilean fishing communities, as well as local groups tied to marine national parks in New Zealand. She added South Africa to the itinerary mid-Watson, as many people she met along the way strongly recommended that Stiles experience South African fisheries as well.

From Vassar to Watson

"I came to Vassar because I could study biology combined with other coursework. Putting together my interests at Vassar was like putting together my project for the Watson. Both were flexible and creative…The Watson showed me that science can be applied, and it made me think broader and more creatively in terms of what I can do with my life."

What now?

Stiles devoted her professional life to a water clean-up plan for the state of Washington upon her return to the U.S. In September, she migrated south to begin a graduate program in oceanography and marine ecology at the University of California at San Diego.

Jesse Stiles ’00

Watson Project

Investigating and creating for the electronic music/art scene. "What I got was the best music I’ve ever written, and what I gave was the best music I’ve ever written."

Watson Locations

England, India, and Australia

Why?

"I started writing music with computers as an aside to the terrifically awful rock bands I played with in high school. It didn’t take very long before I was totally hooked on the synthesizer lifestyle, it was just the most expressive thing I’d ever done. I got really serious about it at Vassar…and the Watson Fellowship is nothing less than the opportunity to consider yourself and your work in the context of the entire world."

Artistic Adventure

Stiles began in London, which he claims is home to the best art and music in the world. In India, he researched "raves" in Goa and traveled in various other states working toward an integration of Hindustani and electronic music. In Australia, Stiles found himself more connected with the community and artistically productive. His favorite Watson moments took place when he was living in Varanasi, a holy city in India. "Varanasi is just packed with temples and holy men, musicians and music, wild monkeys and water buffaloes, sound and fury…I would just walk around with my microphone all day. Everything was full of beauty, and I would steal off with my laptop and integrate some of it into my compositions…I couldn’t have been happier."

What Now?

Stiles said his Watson year was "hands-down" the best year of his life, and that it helped him determine the next stage of it as well. He recently began the M.F.A. program for electronic arts at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Nicole Darling ’01

Watson Project

Documenting and preserving classical dances through photography, photographic collage, and oral histories

Watson Locations

Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos

Why?

"In the West, there is very little awareness or appreciation for the beauty of this region’s art form. Furthermore, in Cambodia and Laos, the classical dances are still in an extremely fragile state due to the countries’ legacies of war and genocide, particularly under the Pol Pot regime. My work is driven by an urgency that is propelled by my passion for the arts and the people in this part of the world."

Status Report

Darling, who lived in Japan before Vassar and spent a semester in Vietnam during her junior year, just recently began her Watson journey. "Already I have learned so much about Thailand, the richness of the country and its people, the culture and the different approaches to life. That being said, I have also learned a lot about myself in the past couple of weeks as I’ve been trying to carve out a new life here. I can’t really imagine where I will be in one year, in what kind of space, but if my life continues at the rate it’s going right now, this will be an extremely rich growing experience."

What Next?

"I can’t keep track of how many people have asked me this question…in truth, I have no idea."

Vassar's Watson Fellows' Topics

1992 Amy Vogelaar Women-Centered Childbirth and Health Care

1993 Karim Ahman Perceptions of Personal Freedom in Post-Communist Russia

1993 Karin Betts Cooperative Living and Communal Responsibility

1994 Michael Ash Photography

1994 Simone Flynn Fiction Writing

1995 Tasha Gill The Veil and the Female Elite in Muslim Societies

1995 Eric McGlinchey Russia’s Economic Transition

1995 Jessica Lawrence Conservation, Education, and Rainforest Communities

1996 Earl Hadley Religion and Economic Development: Allies or Enemies?

1996 Oren Rosenberg Disease Ecology

1997 Nicola Virgill declined Fellowship offer

1998 Cheryl Scheffler Addiction: Treatment, Laws, and Societal Impact

1999 Emily Porter Buddhist Nuns in Transition

1999 Margot Stiles The Tradition, Ecology, and Community of Fisheries

2000 Jesse Stiles Electronic Music

2001 Nicole Darling Documenting Classical Dances

— Veronika Ruff '01