Sampling Women's Education

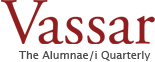

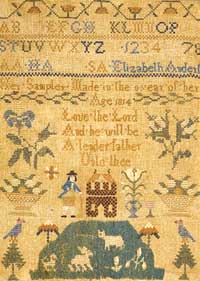

For many, the word sampler conjures up an image of a box of chocolates. Vassar’s sampler collection, though, is of the needle-and-thread variety. Often viewed as homey arts-and-crafts stitchings displaying simple messages such as “Home Sweet Home,” these works of art are, in fact, intricate silk embroideries that were an integral part of a woman’s education from the 17th through the 19th centuries. And Vassar boasts an impressive collection of these needlework gems.

Vassar’s sampler collection is “comparable to the large private collections that form the nucleus of sampler collections in major American art museums,” claimed preservation consultant Joanne Lukacher. Given to the college first in 1920 by Emmeline Reed Bedell in honor of her niece Martha Clawson Reed ’10, and later in 1960 by Elizabeth Gillmer Packard (class of 1894), Vassar’s 315 samplers originate from Western Europe, the British Isles, and North America and range in date from 1660 to 1911 — with the majority dating from the 18th century through the 1830s.

The sampler had various functions. Most practically, it provided an example, or sample, of different types of stitches to be used in the kind of fancy, domestic needlework middle-class women were expected to master for marriage.

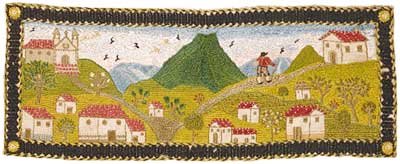

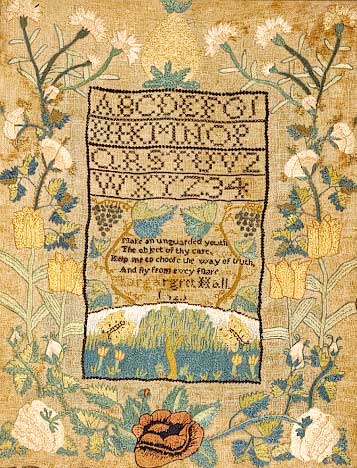

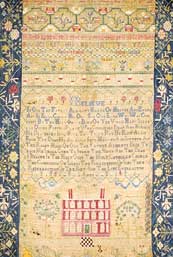

Teachers often chose and modeled the sampler designs, which students then copied. In fact, the ability to date and trace the origins of samplers often involves identifying a regional or a particular teacher’s “style” and matching samplers with that style. However, space for self-expression did exist in what Lukacher called “the traditional vocabulary of the sampler.” Girls often had the freedom to choose the quotation or verse they stitched onto their samplers. These expressions — commonly taken from sources such as hymn books, verse books, and even the Bible — focus upon and reveal a kind of consciousness about gender and domestic roles in the 19th century, the heyday of sampler production.

Lukacher also mentioned the details of the needlework, such as an attention to color or the quality of the stitching. “These details provide the clues as to whether this girl was just learning or was a refined needleworker. A real sense of the individual is apparent in samplers.”

Some of these samplers are products of ladies’ academies, the “finishing schools” where middle-class daughters learned the female accomplishments of singing, dancing, art, and ornamental needlework. “The sampler was often the most important token taken away from these academies by the girls, both for its practical importance and the way it proved a girl’s marriageability or proper femininity, often expressed through the verses stitched onto the samplers,” said Susan Zlotnick, associate professor of English. “The samplers both prescribed and described model femininity. Emphasizing literacy, piety, docility, and devotedness to parents, samplers essentially reinforced the idea that a young woman would make a good wife.”

What kind of special value do these samplers add to Vassar’s art collection? “Samplers say something about the pre-history of Vassar,” said Zlotnick. “In the 18th and increasingly the 19th century, before institutions like Vassar existed, these ladies’ academies provided one of the few spaces for women’s education. The sampler physically represents how much this education was essentially an education in domesticity and femininity. The creation of Vassar grew out of the feeling that the limited skills being taught at these academies were not sufficient in educating the women who were meant to be moral missionaries for an entire society.” Preservation consultant Joanne Lukacher added, “It is important to remember that the women educated in this context were the grandmothers, mothers, and teachers of the first Vassar students.”

Zlotnick put Vassar’s sampler collections to good use in the spring 2000 exhibition, Modeling Femininity, which she co-curated with Francesca Consagra at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center (FLLAC). The exhibition, which explored the way in which art in the 19th century influenced moral education, especially for women, had one room devoted entirely to samplers. “Of the three rooms in the exhibition,” Zlotnick said, “people loved the sampler room. These are rich, dense texts to be read. People want to take time with them.” Zlotnick and other faculty members would like to see the samplers more accessible for educational and scholarly purposes. “Ideally, the samplers would have their own permanent, rotating gallery,” she said.

While many of Vassar’s 315 samplers are in good condition and retain their vibrant colors, others have suffered the damaging effects of age. Moving the samplers from the library and the basement of the old college art gallery into the climate-controlled environment of the FLLAC has retarded some of this damage. Kimberly Leath ’92 and Carolyn Priest-Dorman ’81 contributed to the effort to prevent further damage when, under the guidance of Joann Potter, collections manager for the FLLAC, they began in-house conservation efforts based upon recommendations made by the Textile Conservation Workshop condition survey of the 1990s, which involved wrapping and properly storing the samplers in print cabinet drawers. But about 50 of the samplers remain in dire need of immediate preservation, and all samplers in Vassar’s collection require basic conservation cleaning and remounting to prevent future deterioration.

To assist in these remaining efforts, Lukacher, with the help of sampler scholar Glee Krueger and needlework expert Patricia Moore, voluntarily began a large-scale project in fall 2000 to help preserve and conserve Vassar’s sampler collection. This project has involved not only taking full stock of the condition of each sampler and identifying certain samplers as conservation priorities, but also carefully studying and cataloguing the samplers and thereby correcting several misidentifications in the original information available on the samplers.

Along with Potter, Lukacher traveled to South Salem, New York, to consult with the professionals at the Textile Conservation Workshop in May 2001. The two spoke with conservators and gathered professional opinions about, among other topics, storage and display options for the samplers. This trip solidified the necessity of making Vassar’s samplers a top priority for conservation. “In quality and breadth, this is a major sampler collection. Handling the samplers now, in their present state, contributes to the rate of deterioration,” noted Lukacher.

As with any conservation project of this scope, available monies determine the extent to which conservation can be realized. And while a few samplers are currently being treated and remounted, efforts to save Vassar’s samplers have a long way to go.

To learn more about the sampler adoption project, contact Altegoer directly at dialtegoer@vassar.edu. For those who will be on campus for Reunion 2002, on the afternoon of Friday, June 7, Zlotnick and Lukacher will present the history and importance of Vassar’s sampler collection and Vassar’s efforts to preserve it.