Looking Back and Looking Forward

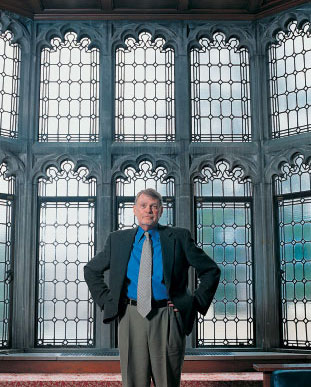

"THE MANTRA THAT I CURRENTLY RECITE," COLTON JOHNSON TELLS ME, "HAS THREE PARTS."

"I am coming to the end of my second five-year term as Dean of the College.

I was 65 last October.

It would be absurd — bordering on the obscene — to think that I will be doing this job when I am 70."

Three simple reasons for leaving his position as dean of the college, he claims. Three simple reasons why he is stepping down from the latest in a series of prominent, influential positions on our Poughkeepsie campus. And he adds part four, one certainty about the future, "that my wife of 44 years does not want my undivided attention."

Loitering alone in Johnson's unassuming office — he has gone to ice his shoulder after one of his regular (and intense) squash matches - gives one the opportunity to consider the man who has had more impact on the character and mission of Vassar than many committees, commissions, and offices have collectively. There are mementos strewn about the simple, white-painted bookshelves: photographs of friends and family, invitations to bygone events and ceremonies, a shiny gold medal in a display box, a delicately folded, bold green sweater. And books by and about W. B. Yeats. Everywhere.

As dean of the college, Johnson has had less time than he'd have liked for active teaching. Nonetheless, the specialist in modern English and Irish literature was able last semester to teach a seminar on Yeats, based on material from his recent book, volume X of the Collected Works of W. B. Yeats. He enjoyed it so much that he hints he might try to put together another class after he leaves his dean position this summer. Johnson, in fact, has no intention of retiring as a faculty member just yet. He's hoping to keep an office on campus as well as his study in the library. And, for the moment, he has no specific plans for a sabbatical (how could a man who has taken only one six-month sabbatical since 1975 know what to do with his free time?). Among eventual activities are Vassar and Yeats research projects and sorting through decades of files in preparation for their review by Vassar's archivist.

When Johnson, who earned all of his degrees from Northwestern University, arrived on campus in 1965, he didn't think he'd be here for more than a couple of years. "It was an odd time to be on the market," he remembers. "I had 16 job offers, ranging from UVA and UCLA to Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart. My mentor at Northwestern assured me that my career would be in the university world, but said teaching at Vassar for a year or two would be a good chance to learn how a college works." Vassar hired Johnson before he had started his dissertation.

Within the first years of his arrival in Poughkeepsie, he witnessed some dramatic changes at Vassar. The college was mulling over issues of identity; first and foremost, could Vassar continue to exist successfully as a single-sex school? Would an unprecedented move to coeducation destroy the college, or would it enrich it? These were serious questions that were debated daily, but Johnson confesses he did not focus as much on them as others did at the time. "I was still trying not to get fired," he deadpans.

From Johnson's viewpoint, Vassar's decision to go coed was driven largely by geography. Most women's colleges, he noted, had formed some sort of relationship with men's colleges that often led to their absorption. Brown had Pembroke, Harvard nearly had Radcliffe, and each of the other "Seven Sisters" was located close to one or more men's colleges. The closest place to Vassar was West Point, and "that wouldn't really have worked," Johnson pointed out. Going coed, he added, was "probably the only logical step. However, the times — economic and political, combined with our own extraordinary fame as a women's college — made this more of a challenge than perhaps any other college's transformation."

But "Vassar is infinitely better as a coeducational institution," Johnson notes — in part because that decision was not the only major change the trustees had to face in 1969. Two other strategic goals — increased diversity in the faculty, staff, and student body and a complete review and modernization of all aspects of the college - continue to shape the college today. "The success [of these three initiatives] is undeniable," Johnson stated. "The curriculum is far more complex and interrelated and the community more diverse and inclusive, and yet the changes led — even if not always smoothly or predictably — to an institution that has many of the most desirable hallmarks of the old Vassar."

The reorganization of the college also had a personal impact on Johnson, setting in motion policy changes that led to his present post in campus administration. The entire cocurricular side of Vassar developed rather peculiarly and rather late compared to its peer institutions — partly because it was a women's college, but also because of personalities involved.

Elizabeth Drouilhet '30, a campus institution in the middle decades of the 20th century, was a powerful woman, already deeply entrenched in the Vassar psyche, when Johnson arrived. "She was essentially everything aside from the business office and dean of the faculty," Johnson notes. She came to campus as its warden, a role that evolved into the now-defunct office of Dean of Residence. Referring to contemporary offices, Johnson observes that "ResLife, Campus Activities, probably even health services reported to her." (Even as late as 1975, when Johnson became dean of studies, there was no dean of students and no fully articulated set of student resources outside of the curriculum, no doubt partly because Vassar had been so dependent on Drouilhet's strength and ability.)

In turning to coeducation, the college needed to reorganize and modernize, but had to do so quickly. Despite its status as one of America's most established colleges for women, the school's physical plant and academic resources had simply not grown at the pace of its peer institutions. One of its first moves was to introduce a new office — the vice president of student affairs — and in 1975, Dean of Studies Natalie Marshall '51 was asked to succeed the first student affairs vice-president, John Duggan. Johnson, married with a young child and living in Rhinebeck, New York, was newly tenured and busy teaching literature and writing, and had not envisioned himself an administrator. Until, he recalls bemusedly, "I got a call early one morning from Alan Simpson."

Simpson, then-president of Vassar, told him a search committee had recommended Johnson for the position of dean of studies, and encouraged him to accept the invitation. Johnson rationalized that he would keep his office in Avery Hall, his advisees, and his senior seminar and only do this work for three years. He would not think of himself as abandoning one thing and starting another. Reluctantly, he took the job.

Realignments of campus administration had been but one of many changes that the new Vassar undertook. Indeed, the development of a vibrant, coeducational campus had a long way to go. Letters from Vassar girls of the 19th century are replete with descriptions of lectures, activities, symposia, debates, and other activities designed to fill the girls' time out of the classroom. By the time Vassar went coed, however, the relaxing of campus restrictions (including travel regulations) contributed to the development of a culture of desertion. When Johnson came to Vassar, the Retreat, for example, closed at 4:30 on Friday afternoons and did not reopen until Monday morning, and the library also was closed for much of the weekend.

The administration was not blind to this problem (and it was by no means the only significant issue facing the campus), and it searched for ways to develop a new set of resources for the "cocurriculum." What was needed, Johnson explains, was "not necessarily a separate bureaucracy, but an organized set of resources." Recognizing this need shortly after taking office, President Frances Fergusson had substituted a dean of student life for the student affairs vice-presidency, and in 1991, when the first dean of student life, James Montoya, resigned, Johnson was asked to step in for a year.

Then he was asked to stay a second year. And finally he was asked to just stay, as Vassar's first dean of the college. The appointment, he knew, would facilitate the types of far-reaching changes he had been eager to implement. In the next few years Johnson, with Acting President Nancy Shrom Dye '69 and then with President Fergusson, helped develop a new model for Vassar's cocurriculum.

The model also allowed for the creation of new resources, and Johnson — who had developed an interest in Vassar's transfer students — initiated discussions with LaGuardia and Dutchess Community Colleges, to see if there was interest in developing some type of cooperative program with Vassar.

One of Vassar's key goals after 1969 was increasing diversity — "which we largely understood as race in those days," Johnson says — and the college was still grappling with this issue in the 1980s. Vassar vied with Wesleyan, Dartmouth, and others for the few students of color that had found their way into prep-school programs designed to identify students of promise in inner cities and prepare them for the Ivies. This limited pool of students was avidly sought after, but few colleges or universities had thought of working to expand it.

The focus on racial diversity coincided with Johnson's interest in creating more resources to draw community college transfers — many of whom were eager and qualified students of color — to Vassar. In 1984 he conceived of a summer program that would introduce promising community college students to residential college life. They would enroll in classes devised and taught by both Vassar and community college teachers. The experience would be immersive: students would live in dormitories, eat in dining centers, and experience "2 a.m. bull sessions." Much research at the time suggested that liberal learning on a residential campus, after all, took place in many spaces between classes: the concept of a cocurriculum was increasingly central to the college experience.

The program, dubbed Exploring Transfer, was finalized after a meeting in then-President Virginia Smith's conference room — she had obtained money from the Mellon Foundation ("thankfully, because I had no idea what I was doing!" Johnson notes) — and the program developed quickly. (Thomas McGlinchey, who will retire this year as a writing specialist, was named coordinator, and was from the start deeply committed to the program's aims.) The college would be giving the Vassar experience to those who did not have access to this type of educational opportunity.

It took some convincing to get the program started. Sometimes the resistance came from the community colleges themselves. Many remarked that they didn't have folks who were the "right type" to come to Vassar. The students, however, were more than up to the challenge. For four weeks, five days a week, they took in the newness of everything — from waking up in a dorm room to eating at the dining center to delving into incredible amounts of engaging reading and writing.

The observations of outsiders were similarly positive. After the program's inauguration in 1985, support from alumnae/i and foundations helped fund program operations as well as establish an endowment. Sometimes, Johnson admits, he found it difficult to explain why Vassar was seeking such funding. It was awkward, for example, to represent Vassar before foundation officers who had just heard Amherst or the University of Pennsylvania ask for money for anthropological research, biology, and the like, and to request money for community colleges. Grant-givers would routinely inquire why Vassar wanted money for something that seemingly didn't benefit Vassar. Of course, the integration of such students into the campus community did and does benefit both the college and the larger community of higher education, and with a little convincing, the foundations and donors became remarkably positive and eager.

In 1989 the Charles A. Dana Foundation presented Johnson and LaGuardia Community College's Janet Lieberman with the Dana Award for Pioneering Achievement in Higher Education, a major award in the field. And now, almost 20 years after is inception, the Exploring Transfer program is still being hailed as an enormous success. What started as a consortium between a few professors at Vassar, LaGuardia, and Dutchess Community College blossomed into an enduring, inspiring program.

Multiple colleges have explored the possibility of cloning Vassar's program; projects at Bucknell University and Smith College have grown into success stories of their own. Many Exploring Transfer participants became Vassar graduates, and a number have made significant accomplishments post-college. "These are wonderful, inspiring people who continue to be so," he says. (One, he observes, is now a faculty member at an Ivy League school.)

Despite his central role in the project, Johnson is the first to share the responsibility for its success. "Without Tom McGlinchey, without funders, without [the support of Presidents Smith and Fergusson], and without enthusiastic faculty — this program would not exist. And the Development Office recognized that this was consistent with the mission of the college... There has just been enormous support." (Look for a feature article on the Exploring Transfer Program in the fall VQ.)

With retirement from the deanship on the horizon, one might expect Johnson to slow things down a bit. But that hasn't been the case at all. "Colton's dedication to Vassar students is astounding," comments Vassar Student Association President Laura Robertson '04. "In our weekly meetings, he always communicates his trust in the students, and the way in which he hopes that trust and respect is [conveyed] in the regulations and structures of Vassar College."

Johnson is confident in the state of Vassar as he steps down from his administrative role. He points first to the college's much-loved president, Frances Fergusson, and her central role at the college as one reason for this attitude. "Fran is an incredible leader, and the integrity with which she thinks and speaks is extraordinary," he affirms. "The positions she takes on the issues she speaks out on are the same whether she is speaking privately or to faculty, alumnae/i, or accepted students. That's not always the case with college and university presidents, but it's invariably so with Fran. This inspires my confidence in the future of Vassar. The course she's set the college on is a sound one." And President Fergusson is equally generous with her praise for Johnson. "I can only say that I could not have had a better colleague in working on so many projects that benefit students directly. Colton always thinks about what the students need to make them successful in whatever they try to do. And he has great trust in students, making real our belief that our students help to forge the Vassar of tomorrow."

Both related to and independent of the Exploring Transfer program, Johnson feels the serious discussion of issues of diversity on campus is another reason to be positive. Recent activities, he feels, have moved beyond talk of general access (such as bringing more traditionally underrepresented students and faculty to campus) to institutional inclusion; in other words, the dialogue is now about how to create an environment of inclusiveness. He points to a recent visit by Peggy McIntosh, author of the influential essay "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack" as a sign of this deeper commitment. Johnson also stresses the importance of bringing these issues into all aspects of the college, including the classroom and the curriculum. (He relates his own teaching experience to explain how issues of diversity can be touched upon in any class. Class issues during the long struggle for Irish independence, he notes, became racial issues. The Catholic Irish were not only not English, they were also not upper class Irish, and thus were seen as a lower people, a distinct race. Understanding these tensions is essential to understanding centuries of Irish literature. This understanding has allowed for greater discussion of general diversity issues in his class.) Diversity is about more than access and inclusion, he notes; it also includes equity of outcome. This is the next challenge he sees facing the college — but one he knows Vassar is ready and willing to take on.

Johnson's course evaluations from last seminar were gratifying and have encouraged him to consider taking on an active teaching role again. "When I came here on a one-year appointment, having begun as tenuously as anyone might have," he reflects, "I had no idea that I would still be here all these years later. I am so thankful for the extraordinary multiplicity of careers I've had at the college. I have enjoyed being dean of studies. I have enjoyed being dean of the college. I have enjoyed being a professor." And Vassar has enjoyed having him.

As chair of the Board of House Presidents, Jonathan Cruz '05 is intimately involved with fostering a sense of community on campus, and has accordingly worked with Dean Johnson on the Committee for College Life, a "clearinghouse" organization that approves and alters campus organizations and regulations. About Colton, Cruz said, "One of the joys of being a student leader is the opportunity to find similar levels of enthusiasm among those on the 'other side' — the faculty, the staff, the administration. Colton is, without a doubt, one of the most dedicated people with whom I have had the pleasure to work: you can talk to him about the Vassar experience, and he'll go on with endless energy, rare even in the newest arrivals on campus. As someone who loves the history of the college, it's a secret pleasure of mine to have someone who is not only willing to hear me ramble on about it, but to talk to someone who can fill me in on the details I didn't know."