The Science of Writing: Michael Specter '77

Eighteen grad students in a science-writing course at Columbia University’s journalism school hung on Michael Specter’s every word one rainy Tuesday morning last spring. They were rapt, practically drooling. Specter ’77, a staff writer at The New Yorker, has many journalists’ dream job: months and seemingly unlimited resources to research, report, and craft in-depth articles on important topics that truly affect our world today. Specter gets paid to investigate AIDS, our dwindling water supply, and the spread of bird flu. “I love my job. I travel, write about what interests me, and get published in a place people take seriously,” he said. “There’s nothing I’d rather be doing.”

On salary at the famed magazine, Specter writes four or five extensive science features every year—each 10,000 words or so, usually on serious topics: hackers, malaria, the Bush administration’s politicization of science, and, most recently, AIDS in South Africa and the loss of free speech in Russia. But Specter is also known for the profiles he writes for the magazine, often on Italian designers—Miuccia Prada, Valentino, Manolo Blahnik—an interest born out of his time reporting from Rome for The New York Times. “I need a break from the serious, profound, depressing, world-is-coming-to-an-end journalism I usually do, and I find it in ladies clothes,” he joked. “The profiles are about the people, though, really. I don’t know a lot about fashion.”

Specter has an office with the rest of The New Yorker staff in the Condé Nast building at Times Square, but he prefers to write at home, in the mornings. He limits himself to 1,000 words a day. “I’m old, my brain gets tired,” he explained. “I mean, I can write more than that when I have to—but it’s much better if I don’t.” Since Specter prefers to start writing about two weeks before his deadlines, he uses the remainder of the three months or so he’s given for each assignment to research and report exhaustively.

“This is the luxury of the job: I have time and resources to read and go places before writing,” Specter said. “It’s a ridiculously spoiled lifestyle. I can basically point to a place or a topic and then write about it.” (You see why the budding journalists were jealous.)

Once he and his editors decide on a story topic, Specter spends weeks reading everything he can find on the subject. He also identifies experts in the field who can advise him. Though he’s never had a formal science education, Specter writes on complicated science topics, like waterborne diseases and environmental degradation. He has learned a lot about science by writing on the topic for the last 20 years, but still finds he needs guidance. “I look for people who are really knowledgeable on topics, but who are also good at communicating their knowledge,” he said. “Journalists really need to find these people—they’re rare.”

Because The New Yorker places a strong emphasis on firsthand reporting, Specter actually goes to the places that he writes about. Specter traveled to 11 countries for his story on malaria. And for his February 2005 feature on avian flu, he went to a small village in Thailand to meet a family that lost a mother and daughter to H5N1, spent days with public health officials and government ministers investigating the outbreak in Thailand, and interviewed farmers who raise ducks and chickens in the Thai countryside suspected of spreading the disease. He met with influenza specialists at the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. He also went to Geneva, Switzerland, to discuss the potential epidemic with experts at the World Health Organization.

But at times, he said, three months and eleven countries can be excessive. “I do lots of reporting for my pieces, but there’s such a thing as too much. It takes a while to develop the knack for knowing when to stop researching and when to start writing.” One Columbia student asked Specter how he organizes his thoughts and composes these long 10,000-word features. He told her he thinks of his stories as an orchestral piece: “There are several movements, but they need to be tied together with a constant narrative that runs throughout.”

Specter studied the craft of writing as an English major at Vassar, where he took classes with Frank Bergon and Eamon Grennan. (Grennan’s poems often run in The New Yorker, and Specter said that he “reveres” him.) Specter also credits Dean Mace for training him to work with editors. A British English professor, Mace was “wonderful, but shocking and often just mean,” Specter said. “I went in thinking I was a good writer, but he ripped me down. Luckily, he also built me back up again.”

After graduation, Specter won a Vassar fellowship to study in Europe. He planned to get his Ph.D. at Yale after a year at the University of Warwick, but the job market for professors in the late 1970s was less than stellar, so Specter returned to New York after his fellowship. “Looking back, I’m fairly certain I would have gotten bored staying in one place, but at the time, I wanted to be an academic,” he said. Instead, Specter applied for a job as a “copy boy” at The New York Times. And before long, Times columnist Tom Wicker asked Specter to be his assistant. Wicker told Specter if he performed well, he’d help him get his next job.

Wicker helped Specter land a job at The Washington Post, where his life as a science writer began. When the Challenger space shuttle blew up in 1986, the Post’s science reporter needed help covering the event, and Specter, a general assignment reporter, stepped in. Then when the Post’s national medical reporter moved away shortly thereafter, the editors gave Specter the job because he had developed an interest in AIDS while covering discrimination cases for the paper. “I didn’t even know what a molecule was, but they told me it didn’t matter, I’d learn,” he said. “It was like going to graduate school—the editor took me all around, teaching me about everything.”

Though Specter was thankful that the Washington Post editors allowed him to develop his specialty, he made it clear to them that he wanted to return to New York. As soon as the position opened up, the editors made Specter head of the Post’s New York bureau. But the Times soon lured Specter back. “The Washington Post is a great paper, but on culture, science, and foreign coverage, the Times just puts more resources into it,” he explained. “And those are the things I care about.”

He spent his first year with the Times working from New York on a series about tuberculosis, but he and his then-wife (a fellow Times reporter) were gunning for overseas positions. “They wanted to put us in France, but we wanted a terrible place,” he said, grinning. They got their wish. In 1993 the paper moved the couple to Russia, where Specter became chief of the Moscow bureau during the troublesome years that followed the fall of the Soviet Union. Since foreign correspondents often report through “a prism of their interests,” Specter said, he wrote mostly on poverty and health care. But he had to cover everything, and that included the burgeoning crisis in Chechnya. Specter was one of the first American reporters to interview and write about the Chechan rebels.

Working in Russia—a notoriously tight-lipped place where records are often buried and officials off-limits—has taught Specter a lot about the intricacies of getting people to talk to him, he said. For him, confidence is key. “Confidence comes with practice, but arrogance can also go a long way,” Specter joked. “And besides, now I work for The New Yorker, the most arrogant publication in the world. It exudes confidence for me. People talk to me simply because of where I work. It’s a crutch that writers shouldn’t have.” For one of his latest New Yorker stories, Specter revisited his former home to investigate the gradual disappearance of free speech in Russia and the high-profile murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

The Times likes to move its foreign correspondents around as often as possible. “When correspondents get to a new place, they have fresh ideas, but can be naïve,” Specter explained. “Eventually, they’re smart and authoritative on the subject, but they’re also boring, so the paper gets them the hell out of there.” After five years in Russia, Specter, his wife, and their new daughter Emma were transferred to Rome, from where Specter worked as a senior correspondent throughout the region. While Specter was based in Italy, one of his best friends, David Remnick, became editor of The New Yorker. Remnick and Specter were young reporters together at The Washington Post. Both preferred to pace while brainstorming. They would lap the newsroom—Remnick in one direction and Specter in the other. “Our editors joked that if the two of us would ever sit down and work, the paper might start winning some awards,” Specter said.

Remnick quickly had Specter contributing to The New Yorker, assigning him those profiles on Italian designers. And in 2001 Remnick convinced his old friend to come back to New York for good. Specter and his family returned to the city just one week before 9/11. “I was under the World Trade Center as it fell. Remnick called me when the first plane hit, and I went right down there—I’m an idiot; I’m a journalist,” he said. “I’ve seen a lot of people get killed, but when you wake up in New York, on a beautiful fall day, you just don’t expect to see that.”

It’s a myth that journalists can change the world,” Specter told the Columbia journalism students. “If you want to change the world, you should be a social worker.” He said, for example, that although he’s been writing about AIDS for decades, the issues surrounding the epidemic are more or less the same. “You should be in the business to write stuff and earn money,” he said. “You’ll be bitter if you want to change things.” After the students left, Specter softened that stance slightly. “Some of what I do has some impact because I can tell people about what I see,” he said. “But I do believe that you should be an activist if you fundamentally want to change things.” Still, he does see journalism’s potential for driving social change. “The word is finally out that Bush’s policies are bad and we’re in an internal conflict over it—and that’s largely because of journalism,” he said. “Now we’ll see if people care enough to do something about it.”

Ruff recently finished a master’s program in international affairs and media at Columbia University. She is now an editor for Rodale Magazines International, where she works on the Asian editions of Men’s Health, Prevention, and Women’s Health.

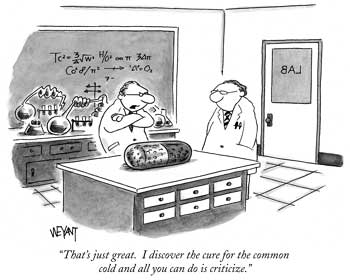

Michael Specter ’77, Staff Writer for The New Yorker. Illustration Credit: © The New Yorker Collection 1999 Christopher Weyant from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved