From Mississippi to Vassar

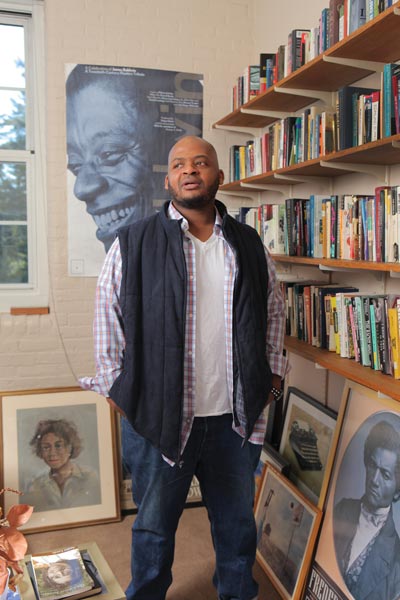

Since his arrival at Vassar in 2002, Kiese Laymon has balanced his position as an emblematic voice of the hip-hop generation with his vocation as teacher. And whether he is writing about heartbreak, family, addiction, the late rapper Tupac Shakur, or gun violence, the associate professor of English offers the same authenticity and generosity to his growing readership as he does to his students.

With his writing, Laymon, who grew up in and around Jackson, Mississippi, pays homage to the multiple worlds in which he has been formed as a writer. “I’m not one of these black Southern people who says ‘I just want people to see me as a writer,’” he says, alluding to others who prefer to disassociate themselves from racial descriptors. “I come from a black Southern tradition. I’m responsible to it and it is responsible for me.”

His influences, however, are myriad. In addition to the likes of novelists Richard Wright and Jesmyn Ward, he names authors James Baldwin and Flannery O’Connor, rapper and music producer Big K.R.I.T. (a fellow Mississippian), filmmaker Ava DuVernay (the first African American woman to win the Best Director prize at Sundance), as well as author and interdisciplinary scholar Imani Perry.

Now, Laymon, whom some have called a refreshing provocateur, is inspiring audiences of his own. He earned wide acclaim last year after an excerpt from his forthcoming book—named after his essay “How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America”—was published at Gawker.com.

The essay is about his experience as a young black man in Central Mississippi, and in it, he writes about the literal and metaphorical violence one associates with guns and death. “I’ve had guns pulled on me by four people under Central Mississippi skies—once by a white undercover cop, once by a young brother trying to rob me for the leftovers of a weak work-study check, once by my mother and twice by myself,” the piece begins.

Like much of Laymon’s writing, the essay resonates because he combines vivid, tragicomic detail and disturbing truths with humor, sarcasm, and personal revelations. In one passage, he describes getting into a car with his high school buddies after having a Filet-O-Fish sandwich, the fish grease fresh on his lips, when a white man wearing a John Deere hat—a man for whom he had just held the door open—calls his white friends “nigger lovers.” The scene that follows—filled with cursing and confusion—is used to illustrate not just Laymon’s lot, but also that of other black teenagers who are disrespected and sometimes killed because of their race—teens such as Rekia Boyd, allegedly shot for “mouthing off” to an off-duty

Chicago police officer, and Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black youth fatally shot in Florida after being identified as “suspicious” by a member of a neighborhood watch.

The essay went viral. As of February 2013, the excerpt had been viewed almost 220,000 times on Gawker, and an additional 80,000 times at Laymon’s own site.

The piece was not only selected by Longform editors as one of the best essays of 2012, but it earned Laymon the roles of contributing editor and writer for Gawker. He now edits essays for an ongoing series and occasionally contributes work of his own. The essay also opened the door to publications at Esquire, ESPN, and Truthout.com. His novel, Long Division, and his collection of nonfiction essays, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, will be published in June and August, respectively.

Laymon was hired as an instructor at Vassar a decade ago, after graduating from Oberlin College and earning his MFA from Indiana University Bloomington. In addition to teaching in the English department, he also is the co-director of the Africana Studies program with Associate Professor of Art Lisa Collins, who says she is always “moved and inspired by his ability to propel students to discover more meaning, purpose, and value in texts and in themselves.”

Former student Tanay Tatum ’12 has experienced this firsthand. She says that in classes like Laymon’s freshman writing seminar “Hip-Hop & Critical Citizenship,” “Writing the Diaspora,” and the senior seminar “Because Dave Chappelle Said So,” she learned not only to critically assess popular culture and media but also to confront herself.

“Not only does Kiese come to class to teach, he also works very hard to make sure you discover something about yourself that you didn’t know before you took his class,” she says. “He forced me and my classmates to confront contentious topics and grapple with them.”

Laymon encourages students to challenge each other to think about issues in a different way, and tries to get them to broaden their perspectives through cross-generational and cross-cultural dialogue.

He is wedded to scholarship, intellectual debate, and the exploration of uncomfortable topics like race. This is evident in his organization of programs such as a fall panel that explored affirmative action in higher education and a conference titled “Necessary Tension,” which brought critics of popular culture, including video blogger Jay Smooth and author dream hampton, to campus on the weekend after Hurricane Sandy. Such events are popular with students, faculty, and administrators alike.

Assistant Professor of English Hua Hsu, who has worked with Laymon since 2007, says that his colleague has a strong stomach for things that don’t come in pretty packages. Laymon, he says, “accepts that life is messy and complicated, and whether it’s in a meeting or on the page, he’s just trying to be as honest and accountable as possible in trying to think through solutions. It’s the quality I admire most about his writing—it’s both polemical and humble, rigorous yet wandering, contradictory yet forever seeking definitive truths.”

But Laymon may have said it best in his now-famous essay: “I’m a walking regret, a truth-teller, a liar, a survivor, a frowning ellipsis, a witness, a dreamer, a teacher, a student, a joker, a writer whose eyes stay red, and I’m a child of this nation.”