Remembrances

Share your own remembrances of Elizabeth Adams Daniels ’41 on the alumnae/i Facebook page.

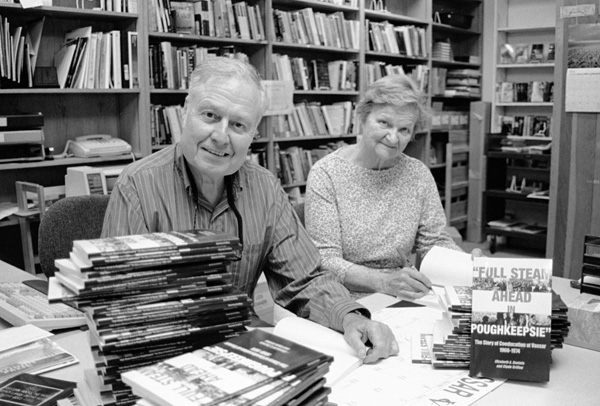

Colton Johnson

Having known Betty Daniels’s friendship for nearly 50 years—I knew her as a colleague in the English department, worked with her when I was dean of studies and she was acting dean of the faculty, and helped her establish the college historian’s office—I have many remembrances and reflections about her.

My wife, Jean, and I remember, first, Betty’s generous hospitality to us and to other people new to the Vassar community over the years. Before we could think of the college as our own comfortable place, Betty’s house on College Avenue and the lively gatherings there to which we were welcomed were just that. Partly because Betty was as long-standing a member of the Poughkeepsie community as she was of the Vassar community, we became acquainted with both. A similar broad and generous cordiality comes to mind when I recall two events, many years later. For her 80th birthday, Betty’s family invited well over 100 faculty, staff, students, and members of the Poughkeepsie community to an afternoon party in the Students’ Building. Beforehand, her daughter Sherry asked if I would be the master of ceremonies at “Vassar Jeopardy,” and when I attempted to wriggle out by swearing I didn’t know anything about this television game show, they sent me the tapes of two shows. In the “competition”—drawn up by Betty herself—faculty, staff, students, and a few brave Poughkeepsieans competed with gusto.

Betty’s 90th birthday celebration was another good party that included town, gown, students, and a special guest—President Henry Noble MacCracken’s daughter Maisry, then in her 100th year. Three members of the faculty—all women—spoke about Betty as a powerful role model; three student academic interns in the historian’s office thanked Betty for the privilege of learning from her; and each of Betty’s three surviving children remembered their childhood and her influence on them. The three students led the room in a resonant rendition of “Happy Birthday.” At the close, I tried to replicate the three-part toast to Betty that her son John had proposed at her 80th, recalling the three words he said characterized his mother: “Vassar,” “party,” and “girl.” John corrected me; the third word, he said, was “animal.”

Betty’s over 75 years’ dedication to the college is an unmatched phenomenon at Vassar.Though her devotion was both steadfast and deep, it was not unquestioning or uncritical. At several points in her time at the college, she compounded and confronted questions of importance to Vassar’s progress. Even in joining the Vassar faculty, for example, she suggested that a mother of four young children could successfully teach in the English department while gaining her doctorate, a model that challenged several conventions.

In 1966, Betty took on the dean of studies job after the first occupant of the recently, and rather imperfectly, created post left—ostensibly seeking the PhD but, the following fall, becoming dean at a nascent upstate college. Betty was also working for a new president, Alan Simpson, who had come from the University of Chicago in 1964 with, many thought, radical plans to reshape the college. It was a tense time, but in an interview with the Misc Betty was characteristically frank and unruffled:

“I … look forward to open discussion with girls about their lives as students. … There are many things to which I feel I must give considerable study. … I am planning a symposium … in late April, which will focus on the relationship of the Vassar student’s undergraduate studies to her postgraduate aspirations. I look forward to finding out what areas require thought and development and doing whatever is in my province so that we will maintain the high standards which the Vassar degree has always meant to me.”

By asking and listening, Betty supplanted the original post with the faculty-based arrangement that her successor deans—including myself—have seen work very well for generations of Vassar students, in all their complexity.

A few years later, all of Betty’s previous Vassar experience influenced her reaction and her subsequent actions when President Simpson announced the possibility of “coordinate coeducation” with Yale. From the beginning, she questioned the prudence of the proposed joint study. But as an alumna, a faculty member, former dean of freshmen, and, effectively, the founding dean of studies, she was indispensible to the Vassar-Yale Study committee.

When several layers of difficulty began to appear, she was trusted by the dissenting faculty and alumnae on one hand and the president and the team working on the Vassar-Yale Study on the other to head the rather hastily assembled Committee on Alternatives. It was this working group that prepared the framework—reshaped into “The Comprehensive Plan” by the Committee on New Dimensions, on which she also served—for what President Simpson would later call “The New Vassar.” Unlike many faculty and alumnae opponents to the Yale merger, Betty remained its productive and thoughtful critic, while, I think, gaining and retaining Alan’s respect. She was his first choice, a few years later, to become acting dean of the faculty when illness obliged Dean Barbara Wells to leave that office.

Betty’s establishment of the office of college historian, after “retiring” in 1985 at the age of 65, was her last and probably most lasting critical contribution to Vassar. Well before her retirement, she had become concerned that much of the documentary evidence of Vassar’s history was in danger of being lost, largely through institutional inattention. And, characteristically, she set out to correct the situation.

Betty wrote about the beginnings of her engagement with Vassar history, and if you haven’t read the piece, I’d recommend it to you. She doesn’t mention her prodigious oral history work in this essay. As she was preparing for her last role at Vassar, she took lessons in conducting oral history interviews and, equipped with a simple cassette recorder, she taped interviews with well over a hundred people, ranging from alumnae, former members of the faculty and trustees, to former employees. I don’t know how she located and convinced such a diverse group of people—many of them with no recent association with the college—to cooperate or how many hundreds of miles she traveled to meet with them, but their words are an invaluable resource for future historians. The original ferric-oxide tapes—whose estimated longevity has dropped from the original 30 years to considerably less than 10—lay idle for many years until, two or three years ago, they were transferred by the Special Collections Library to digital discs. A second set of the compact discs resides in the historian’s office.

Franny “Franny” Prindle Taft ’42

I knew Betty first as a Vassar friend. We were just a year apart and we were tennis friends. Over the years, I played a lot with Betty's husband and [physics professor] Bob Stearns. When the Vassar/Yale study was underway and I was head of AAVC, we were really very discouraged about the probable outcome. It was at this time that Betty was put in charge of a campus committee to study alternatives and possibilities of a Vassar coed college. This was the light at the end of the tunnel and a great morale booster. We were not going to be run over without due process. So Betty became the chairman of saving the Vassar community and a hero on campus. I had kept in touch with Betty over the years and was so respectful of her vast knowledge of the college. I like to think I know a lot of that history, too, and wish we could write another Magnificent Enterprise a la Connie Dimock Ellis ’38. Between those two gals I learned and cherished Vassar’s history.

Riane Harper ’09

Betty took me under her wing early. She hired me as a writer for the Vassar Encyclopedia as a rising sophomore and spent a hot and humid summer introducing me to the Vassar archives, regaling me with tales of the college's early years, and sending me off to the corners of the college community for oral history interviews and soothing cups of tea.

Betty's dedication to the college was inspiring. She knew every fact—and fiction—firsthand. She taught me the value of a good juicy piece of gossip to liven up a historical article; she understood the importance of a human touch to bring dry facts to life. Through Betty, I learned to love Vassar for its quirks and foibles, its contradictions and its long-held convictions.

She may not always have understood how a website worked, but she had a vision for our encyclopedia all the same: to capture the dynamic, vibrant story of her home. Her sharp edits taught me how to write; her passion for the college taught me how to love a place like you'd love a person— warts and all.

Through it all, Betty was patient, quick, and dedicated. She was there every day, rain or shine, to read our work and guide our research. For the rest of my college career, I worked to help Betty build her encyclopedia. Its extensive scope and honest presentation of the highs and lows of Vassar's 150 plus years are an apt legacy for a woman brimming with knowledge and affection for her students and her campus.

Brian Farkas ’10

Betty arrived as a student in 1937—closer to the Civil War than to the iPad. Her involvement with Vassar spanned seven decades, but it was her last job, as Vassar’s storyteller-in-chief, that cements her legacy.

Daniels authored 10 books on the college and well into her 80s, she created the Vassar Encyclopedia, an online compendium of Vassar’s history featuring deeply researched articles on everything from the dawn of electricity at Vassar to biographies of the original trustees. (If you’ve never procrastinated on a paper by surfing http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/, I highly recommend it).

I got to know Betty as her student intern for two years, and then for a research project I did on the history of The Miscellany News. I met with her regularly in Special Collections, before the College Historian’s office got its place of honor in the renovated Old Observatory. I would come with a list of specific questions to fill gaps in my narrative. And sure, Betty could handle those who-what-when type questions. But that wasn’t really why I went to see her. Every query, no matter how simple, was answered with a story—about an old classmate who edited the Miscellany in the ’40s, or a faculty colleague who advised the paper in the ’60s, or an administrator who despised it in the ’70s. In an age of quick access to bits of data, Betty was a woman who still taught and thought anecdotally.

That mattered not just for her career as an English professor but for her second (or third?) career as our historian. Betty knew that narratives shape institutions as much as institutions shape narratives. When she started her historical digging in the 1980s—literally digging through dusty cardboard boxes of records in Main’s basement—Vassar’s narrative had become scrambled. We were historically elite but financially fragile; founded for women but desperately recruiting men; traditionally Republican but suddenly America’s most radical college.

It was Betty who weaved together these torn threads. Through her books and articles, she wrote the story of Vassar as a college founded on principles of access, proud of its heritage but with eyes firmly cast on what’s next. That’s the language used today by Admissions, by Alumnae/i Affairs & Development, and by each of us when asked about our alma mater. It’s hard to know where our understanding of Vassar’s story begins, and our remembrance of her telling of that story ends.

Betty died on January 28. On January 27, the Vassar 150 World Changing Campaign held its celebration dinner in New York. That evening toasted Vassar’s amazing success in raising $431 million, funds that will create new scholarships, support a modern science curriculum, and ensure that our Vassar stays as progressive and magical as we’ve always known her.

There’s a chronological poetry in those hours between January 27 and 28, as past slipped into present into future. It’s easy to imagine that Betty refused to leave without the peace of mind that it was secure for the next generation.

Though Betty will be missed, her tales will hold strong. Her narratives inform the way our college talks about itself, the way our college thinks about itself. Her passing gives way to an immortality—a final merger into this place that she long ago became indistinguishable from.

A version was originally published in the Miscellany News.

Frank E. Giordano ’76

As an alumnus of Vassar, I was extremely saddened to hear of the passing of Dean Daniels. Allow me to tell you what Dean Daniels did for me when I first came to Vassar. Married with a full-time job and two children, I came in as a non-traditional student. I was a Dutchess Community College transfer.

After the first week of classes I had had very little sleep and it was virtually impossible to keep up with my class work. I went to see Dean Daniels to inform her that I was dropping out. She took one look at me and called her secretary to order coffee and sandwiches. Dean Daniels reduced my classes to part time and continued my scholarship. To be sure, if not for her, I would not be a Vassar grad. Dean Daniels was an extraordinary person and embodied the spirit of Vassar tradition.

Laura Green '13

I met Betty in 2011 during my junior year at Vassar when I began working for the College Historian's office. In our weekly meetings, she could always be counted on to clarify murky details of Vassar history and to point us in the direction of new sources for our research. If ever there was a question that stumped the rest of the office, we turned to Betty. I often found myself in some amount of awe at both her encyclopedic knowledge and her deep commitment to Vassar. It was a privilege to work with someone who demonstrated such true and sustained dedication.