Enlisting Women

While many Vassar women made their mark during the 20th century, most are not known for their roles in the military. Yet over the years — and, in particular, during World War II — dozens of alumnae have served their country in the army, navy, marines, coast guard, air force, and as military nurses.

Among the first of these women was Julia C. Stimson 1901, who made a career out of the Army Nurse Corps (ANC), sailing for Europe when the United States entered World War I in 1917. Over the next year she became chief nurse of the American Red Cross in France before being appointed director of nursing services for the Army Expeditionary Forces. During the final days of the war, she oversaw the movements of 10,000 Army nurses and received the Distinguished Service Medal, as well as several other awards, in recognition of her service. Stimson eventually became superintendent of the ANC in 1919, serving in that capacity until she retired in 1937.

During World War I, other Vassar grads opted to join civilian units run by the American Red Cross, Salvation Army, YMCA, and other organizations. Records show that by 1919, 111 Vassar alumnae were involved in some kind of service overseas, working with the Vassar Red Cross Unit, the YMCA Canteen Unit, and various others as nurses, interpreters, canteen directors, administrators, and relief workers. Three Vassar alumnae gave their lives overseas during the war, including Amabel Roberts ’13. The first American Red Cross nurse to die overseas, Roberts was killed in 1918 while serving at a British base hospital in France.

In her memory, her classmates gave four $350 scholarships to Vassar’s Summer Training Camp for Nurses, held in the summer of 1918. Described by Sarah P. Carr ’70 (in the winter 1968 VQ) as Vassar’s “most lasting contribution” to the war effort, the camp trained college graduates to serve as nurses in the United States or overseas. With the influenza epidemic in full swing, the 400 trainees went straight from Vassar to work in hospital wards around the country.

The Navy was the first service branch to open its doors to women other than nurses. The first Yeoman, or “Yeomanette,” as they came to be called, was sworn into service in the spring of 1917. At the insistence of Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels, Yeomanettes — who were recruited to “Free a Man to Fight” — received the same pay as their male counterparts, a tradition the Navy would continue when it called women for service in the next world war.

A wartime recruiting rally held at Vassar in April 1945

When the First World War ended in November 1918, virtually all women were removed from military service, and they were not allowed to re-enlist for more than two decades. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the War and Navy Departments hired thousands of women to handle clerical work, communications, and other support functions. Dorothy Zaring ’32, for example, used her proficiency in French, Italian, German, and Spanish to secure a job as a translator with the U.S. Military Intelligence Service in 1942. Alongside other graduates from schools such as Radcliffe and Bryn Mawr, Zaring worked six days a week and often late into the night, recording troop movements on the Italian coast. After the war ended, she stayed with intelligence and went on to work for the Central Intelligence Agency when it was formed in 1947.

As World War II wore on and more and more men were called overseas, a growing movement called for the military to again open its doors to include women who wanted to serve in uniform. Under pressure from some of the nation’s most powerful women, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Congress created the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in May 1942. By November, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard had all created their own women’s units — dubbed Women Accepted for Volunteer Service (WAVES), the Marine Corps Women’s Reserves, and the Coast Guard Women’s Reserves (SPARS), respectively. All of these except the Army gave women full military status as part of permanent reserve units, granting female recruits the same ranks, wages, and opportunities for promotion as their male counterparts. As a result, said Eleanor Stoddard ’42, the WAAC may have seemed less appealing to college-educated women.

“I don’t think Vassar had very many people in the WAAC,” said Stoddard, who has conducted hundreds of interviews with women who served in the military during World War II. “On the whole, college women went into the WAVES, mainly because you could become an officer.” Vassar’s class of 1942 produced 16 WAVES. (According to Stoddard’s research, the class also boasts a Marine and a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots [WASP], which the Army created in 1943.) Former WAVE Frances Prindle Taft ’42 said joining “just seemed like a natural choice” because there “were so many people from Vassar involved with the Navy.”

One of these Navy women was Mildred Helen McAfee ’20. After receiving her M.A. from the University of Chicago, she became executive secretary of the Vassar Alumnae Association and in 1936 was named president of Wellesley College. When the United States entered the war, she served on a committee that led to the establishment of the WAVES, of which she was then named director.

McAfee felt that she had an obligation to lead the new women’s reserve and encouraged her fellow scholars to become involved in the war effort. “If college women cannot take their place as contributing members of a democratic society, particularly in days such as these, then there is something wrong with them or with the institutions they attended,” she later told an interviewer.

Held in the fall of 1942 at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, the first class of WAVES officer recruits included several Vassar grads — among them Taft and classmate Kay Ziegler ’42. According to Taft, the new officer recruits went through the same training as their male counterparts, learning about Navy history, administration, and regulation. All of the members of the first class were trained in communications, studying systems of coding and decoding messages. The new WAVES went on to staff the Navy’s communication stations. From training camp in December 1942, Taft and Ziegler wrote VQ readers to say that during their “short stay here at Smith, [they’ve] bumped into numerous Vassar women, making mess something like an extensive VC reunion.” Indeed, the first class of WAVES included three members of the class of ’37, one each from ’39, ’40, and ’41, and eight from the class of ’42, including Taft and Ziegler.

Though the communications work eventually became “fairly routine,” the experience “gave me a lot of confidence that I had had enough education to go and learn something new and be able to do it,” Taft said in a 1987 interview with Stoddard. “We were also very full of the idea that women could do what men do. And the Navy gave us a great opportunity to prove that: for many of [the WAVES] it was the first time they got paid the same thing a man did, doing the same job.”

When Taft left the service in 1945, Ziegler stayed on to be promoted to commander and the “top-ranking naval officer in the [Vassar] class of 1942,” according to Taft. Ziegler transferred from the reserves to the regular Navy in 1948, and in 1958 she was honored as the Military Woman of the Year at the naval training center in San Diego.

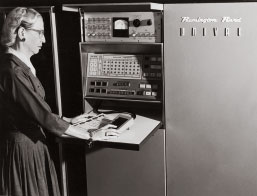

Naval officer Grace Murray Hopper ’28, at work on a UNIVAC, coined the computer term “debugging” in 1945.

One of Vassar’s most notable alums also got her start in the WAVES. Grace Murray Hopper ’28 taught math and physics at Vassar for 12 years before joining the Navy reserves in 1943. During the war she learned to program Mark I, the world’s first large-scale computer, which was used to perform the complex calculations needed to aim the Navy’s most sophisticated guns, mines, rockets, and, eventually, the atomic bomb. In 1945, she coined the term “debugging” after finding a moth stuck in the computer’s machinery. Over the course of her career, Hopper invented the compiler to automate common computer instructions, became the first to start writing computer programs in English, and helped to develop the first “user-friendly” computer language, COBOL, which is still in use today. She was recalled from retirement to active duty in 1967 to help revamp the Navy’s computer system, and in 1985 she was promoted to rear admiral.

Hopper retired in 1986 as the oldest military officer on active duty, having published more than 50 articles on computer programming and becoming the first woman to win the National Medal of Technology. In her honor, the Navy commissioned the USS Hopper destroyer in 1997.

Though many Vassar women, like Taft and Ziegler, may have chosen the Navy as their preferred branch of the military, at least two dozen selected the Army, where “life never gets dull” and “advancement is rapid,” according to Mera Ferrin Galloway ’36. In the January 1943 issue of Mademoiselle, Galloway told readers she was made a company commander just 90 days after her induction into the WAAC. At the time, Galloway oversaw the processing of new recruits who had all joined the Army “to learn to do the jobs which soldiers have been doing so that more men can be sent to the fighting front.” She noted that every WAAC was eligible for overseas duty.

In July 1943, the WAAC dropped “Auxiliary” from its name to become the Women’s Army Corps, allowing women to re-enlist as full members of the military. WACs also started to receive pay equal to men. The Women Airforce Service Pilots was now the only women’s unit in which participants were not actually enlisted in the military and received neither Army titles nor Army uniforms.

The idea for a unit for female pilots had been proposed as early as 1940, when Vassar student Nancy Harkness Love ’35 wrote to Army officials suggesting that experienced women pilots could be used to ferry planes from one place to another. At the time, the idea was rejected; but after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army found itself short on men both to fly combat missions and to ferry its planes.

Vassar’s World War II flying students

In September 1942, the Army created the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadrons and named Love, who had left Vassar after two years to become a pilot, as director. The following year, the Army merged the WAFS and another recently established group, the Women’s Flying Training Detachment, into the Women Airforce Service Pilots. The WASPs were given the jobs of ferrying planes as well as other types of noncombat missions, with Love at the head of the ferrying group. Love was joined by B.G. Everett ’42, who ferried planes and piloted test flights for the WASPs until the unit was disbanded in 1944. Everett continued flying as an instructor until she was killed in a plane crash near the end of the war.

In 1943 another noteworthy alum, Julia Estelle Hamblet ’37, became the first woman from the District of Columbia to join the Marine Corps. She quickly rose from first lieutenant to major, eventually becoming the director of the postwar Women’s Reserve. At the age of 37, she became the youngest director of women in the armed services as the head of the Women Marines, a position she held from 1953 to 1959. Hamblet retired in 1965, having been appointed to the rank of colonel and awarded the Legion of Merit.

By the time the women’s military branches were dissolved after the war ended in 1945, roughly 144,000 women had served in the WAC, nearly 91,400 in the WAVES, some 12,150 in the Marine Corps, and about 11,000 in the Coast Guard. Another 1,074 served as WASPs, and more than 68,000 in the Army and Navy Nurse Corps. In all, approximately 338,000 women served in uniform during World War II. The women’s reserve units became permanent, but separate, parts of the regular armed forces in 1948 and remained that way until 1978, when women were fully assimilated into all but the combat branches of the U.S. military.

Though not every Vassar woman who served during World War II decided to make a career out of the military, the experience would nevertheless last a lifetime. “Perhaps, probably, undoubtedly, the one external event of the past 50 years having the greatest impact on my life is World War II,” wrote former Marine Jean Carpenter ’42 in her 50th class reunion biography. “[The experience] was an awakening for me, an eye-opener, and a real awareness of what life is all about.”

Olivia Mancini ’00

Olivia Mancini ’00 currently works as a senior staff writer for the Advisory Board Company in Washington, DC.

France Honors Vassar

During World War I, the Vassar community raised thousands of dollars for the French war effort and sent more than 100 to serve overseas with Vassar’s own nurses unit, the American Red Cross, or the YMCA. To thank the college for the help of its students, alumnae, and faculty, on November 6, 1920, the French government gave Vassar one of the tanks it used in the war. The tank was placed on the lawn outside of Josselyn House where it remained until being removed during the 1940s. According to college historian Elizabeth Adams Daniels ’41, some students found the military vehicle useful as a place to store their bootleg liquor during Prohibition. One Vassar legend has then-President Henry Noble MacCracken catching sight of a student slipping from her dorm window after dark to remove her stash from the tank. When he saw her struggling to get back into her room, he “stepped out from the shadows and gave her a heave” — or so the story goes, said Daniels.

Cryptography Course Concealed!

World War II provided opportunities for women to become involved in areas typically dominated by men, particularly in the areas of math and science. Looking for a way to replace men working in communications and cryptography, the U.S. government determined that women actually performed certain tasks better than their male counterparts — specifically those that required patience and attention to detail, such as decoding, said Vassar Associate Professor of Mathematics Benjamin Lotto. Perhaps in an effort to ensure a steady stream of college educated women to staff their communications departments, Navy officials approached Vassar Dean C. Mildred Thompson sometime in 1942 for permission to develop a secret elective course in cryptography that would train Vassar women talented in math and languages to enter the Navy upon graduation. According to Lotto, who first stumbled across a reference to the course in a book on the history of cryptography, Vassar was one of a handful of women’s colleges that offered the course at the Navy’s request sometime between 1943 and the end of the war in 1945. Though little is known about the secret class, which was taught by Vassar math professor Mary Evelyn Wells, Lotto estimated that anywhere between 10 and 50 students took the course to receive college credit — though it is not known how many actually went on to join the Navy. Lotto said he has tracked down three Vassar women who participated in the course but is looking for more. If you have any information or know of anyone who may have taken the class, please contact Lotto at 845.437.7180.