Rare Books and the Vassar Curriculum

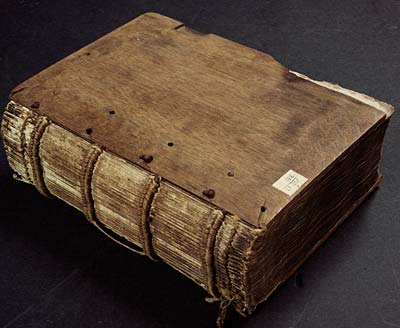

In a corner of the library that is furthest from its main entrance, secured behind a number of specially locked doors, and resting in the cool comfort of 69 degrees Fahrenheit and 49 percent relative humidity, lie approximately 25,000 books, which together make up the college’s rare book collection. The volumes are neatly housed according to size (for preservation reasons), and many of them can be accessed only through a card catalog. This is a wonderfully quiet world, where books lie in slumber. Or is it?

Books are meant to be used, and Vassar’s librarians continually look for ways to integrate rare books into the college curriculum. This effort actually has a long tradition at Vassar; it is closely connected to the work of professors like Lucy Maynard Salmon, one of Vassar’s earliest history professors, who pioneered the use of primary sources in the classroom. This tradition has continued at the college, having been passed down and renewed among succeeding members of the faculty. Indeed, one may go so far as to say that an enduring hallmark of a Vassar education is the ability to “go to the source,” whether that is a work of art, a piece of music, or a rare book.

One of the key features of the library’s Archives & Special Collections Department is the Elizabeth Adams Daniels ’41 Seminar Room, a dedicated space for teaching. Each semester a variety of classes are held there, providing opportunities for students to examine, up close, titles from the rare book collection. These classes have represented a number of academic departments and programs, including Africana studies, art, education, English, environmental studies, geology and geography, German studies, history, media studies, Medieval and Renaissance studies, and Victorian studies.

In spring 2004 Robert DeMaria, Vassar professor of English, and I took things a step further and offered a course titled “The Medium of Print and the History of Books.” It provided a historical review of books produced from the 15th century to the present, an introduction to the physical aspect of books (binding, paper, typography, and illustration), and a consideration of related topics, such as the role of authors, readers, and collectors. Almost every session included an examination of books from the rare book collection.

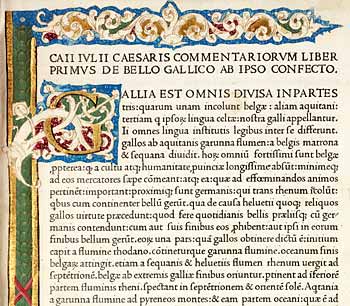

Julius Caesar Works, printer Nicolas Jenson, 1471

Vassar’s holdings in this area are sufficiently rich to support a variety of investigations. For example, students of the Renaissance examine texts put out by the famous humanist Aldus Manutius; those studying the Reformation look at original texts of Luther and Calvin; introductory geography students work with rare maps and atlases published during the Age of Exploration; English majors examine Shakespeare folios and first editions of 19th-century English writers like Dickens and the Brontë sisters; Africana studies majors leaf through an inscribed copy of Phyllis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral; those from education complete assignments using children’s books; and media studies students compare various printed editions of Gulliver’s Travels.

Vassar’s rich rare book collection has developed through gifts, bequests, and purchases. The bulk of the collection building, however, has taken place via gifts, particularly from Vassar alumnae from the early and mid-20th century. Without the generosity of these people, the collection would not be anything close to what it is today.

Still, there remain certain gaps in the collection. We are especially interested in adding more examples of early printing from the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries; high points in British and American literature; books produced by small presses in the U.S. and abroad; and artists’ books. We would also consider collections that might support other areas of the curriculum in new ways.

It is of course a joy to acquire rare books, to catalog them and place them next to their bibliographic relatives on the appropriate shelf; but it is an even greater pleasure to know that these items will be shared with students and other researchers eager to learn from their special properties and characteristics.