Hidden Histories

Every location on campus has a million stories — some well known, some less so. Here are a few chestnuts we’ve recently dug up, with help from Special Collections and the online Vassar Encyclopedia, among other sources.

WELCOME HOME Blodgett Hall — or “the Euthenics Building,” as it was once called — began life with grand plans. Along with Cushing, Kenyon, and Wimpfheimer, it housed Vassar’s ambitious but doomed program in “euthenics,” the science of “the development of human well-being through the improvement of living conditions.” Built in 1928, the design included classrooms, labs, studios, and a special accomodation for the building’s donor, Minnie Cumnock Blodgett, class of 1884: a “model apartment for the study of interior design and efficient housekeeping” — which was also intended to be "Blodgett's residence when she visited the campus."

OKAY SMART GUY In 1940, a Vassar girl had “a sure-fire way to mystify a Harvard man.” She would take him to the “betting bridge” over the stream between Sunset Lake “and the service building outlet. Ordinarily, the stream would flow south” — but service-building steam “bubbles into a fountain in the middle of Sunset Lake, which, spouting hot water, forces the surface current back up north. When Johnny Harvard wagers that it flows south, Vassar triumphantly throws a twig in the water and watches it borne in the opposite direction.” Whether bafflement was intrinsic to wooing remains unclear.

A CLEAN HISTORYMany campus buildings have lived through various incarnations, and Swift Hall — originally Swift Infirmary — is no different. (In its first life, students nicknamed it “Swift Recovery.”) When the history department moved in in 1941, the Misc called the change “a complete revamping,” noting that the “three old wards” had become “big classrooms,” and “Venetian blinds” had been added “‘to give the modern touch.’” Perhaps especially important for a building that had recently housed the unwell, though, was the important detail that “[i]nside, the walls [had] been washed." Always a good idea.

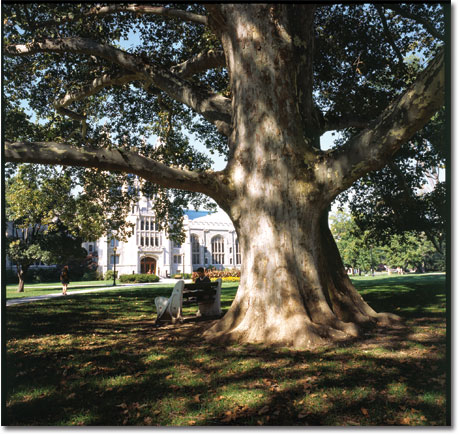

BURIED SECRETS? In Vassar’s early years, the class tree ceremony was “a cultlike event held in secret with elaborate costumes and dances” that “culminated in the burial of the class records and relics next to or under the tree.” The plaque by this London plane tree claims it for the Class of 1906; are their records entombed here? Maybe, but horticulturalist Jeff Horst suspects that any lost treasures would have been “pushed up and out of the ground” by the tree’s roots. (Horst can confirm the practice, however, having discovered a buried metal box while relocating a class tree; its contents, he says, were "completely deteriorated.")

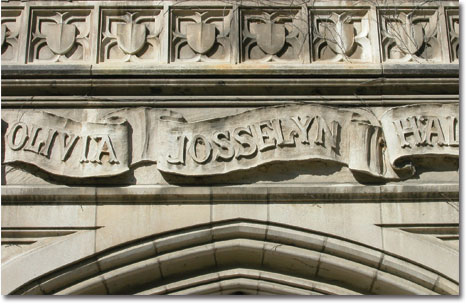

JOSS BEACHHEAD Two years after the end of the Great War, France gave Vassar a tank. (This was 35 years after the Statue of Liberty arrived in New York harbor; France doesn’t give presents like it used to.) The tank sat on the lawn in front of Josselyn House “until the summer of 1934, when it was dismantled.” While being taken apart, “workmen found in the tank an unexploded fuse cap and a considerable amount of benzene” — so if the legend of students secreting themselves within the 40-ton Saint-Charmond for an illicit cigarette is true, then “the smokers were lucky indeed."

DOUBLE VISION Noyes House “was intended to be the first of two identical

OTTOMAN RHAPSODY Skinner contains many treasures — even treasures within treasures, such as the contents of the Historical Musical Instrument Collection, kept on rotating display on the third floor of the music library. The collection includes an early-1800s Giraffe Piano, so-called “because of its asymmetrical, curvaceous case,” like “a grand piano standing on end.” (Henry Ford wanted it; Vassar got it.) One of its many pedals is for a bell “which lent exotic color to popular music such as Turkish marches, much in vogue at the time.” Less portable than an iPod — but a lot more impressive.

GARDEN MIX Vassar has a long history of interdisciplinary studies — including early joint work between the humanities and the sciences. The plan for the Shakespeare Garden “originated with Miss Winifred Smith and Miss Emmeline Moore of the Departments of English and Botany, and the first planting of pansies was made by the Shakespeare and Botany classes” on April 24, 1916 — “the day after the anniversary of the poet’s death.” Perhaps current classes in, say, T.S. Eliot and Ecology could derive inspiration from their example (a "Waste Land Garden," anyone?).

Photo credit: Courtesy of Vassar College

Have comments about this article? Email vq@vassar.edu