Digging Deeper

Farming's Next Generation

Pablo Elliott ’00, an Africana Studies major at Vassar, had no intention of becoming a farmer. Before he was born, his parents bought Stoney Lonesome Farm in Gainesville, Virginia, 35 miles outside of Washington, DC. But Elliott says, “It was never a business for them—they had a few horses and some cattle, but that was it.” The family moved closer to DC a few months after Elliott’s birth and rented the farm to tenants. Over the years, the land became overgrown, and by the time Elliott reached high school the family had stopped renting the farm altogether. As a high school student, Elliott began visiting the farm over summer breaks and continued during college. “I just liked the farm setting and being at the farm,” he says, but the “whole farm-as-career thing” really did not occur to him until later.

Elliott got his first real taste of growing the summer before his senior year at Vassar, when he served as the first intern at the Poughkeepsie Farm Project (PFP). Located on the Vassar Farm, the nonprofit CSA (community-supported agriculture) program allows Poughkeepsie-area residents to buy “shares” in the farm and then reap a portion of weekly harvests throughout the growing season.

Elliott describes his decision to go into farming this way: “Six months of a postcollege internship at a Washington, DC, nonprofit or corporate environment will make any reasonable soul yearn for some fresh air!” So, after a brief stint at an indoor “urban” job, he moved to Stoney Lonesome Farm and formulated a three-step plan: “Season 1: Start a garden. Season 2: Sell something. Season 3: Make it work.” Elliott began with a tiny kitchen garden before expanding to an “ambitious” one that spanned ¼ acre. He sold tomatoes to some neighbors in the second growing season. He now admits that back then he had no idea how to realize the third step in his plan, or what “making it work” actually meant. Elliott, a guitarist and drummer, had a vague, but “fairly romantic idea of playing music and selling vegetables.”

Things started to come into focus when Esther Mandelheim Elliott ’01, who had been laid off from her job in New York City, came down to Stoney Lonesome for a party packed with Vassar grads. As Elliott describes it, “She had some time to kill and ended up volunteering. Eventually, she just stayed on the farm and we decided to start a CSA the next spring.”

Before embarking on their new venture, they went to a one-day workshop on developing CSAs offered by an organic farming association—and they were off. “We didn’t know what we were getting into with a community farm, in terms of the intensity of the demands and the pressure,” says Elliott. “We didn’t realize that starting a CSA was like getting married, essentially.” But the level of commitment to each other, to the business, and to the land only grew stronger. The two took a break from weeding for their wedding in 2006.

Like her husband, Mandelheim Elliott had no idea she’d one day be living the farm life. She had studied political science at Vassar, and prior to her work at Stoney Lonesome, had had no farming experience. She and her family had emigrated from the former Soviet Union in 1989, when she was 10. She didn’t know any English, but learned it, along with Hebrew, over the next two years in a New York City Jewish day school. She then went on to a modern Orthodox high school of about 120 students.

Her parents, she says, “certainly had high hopes of a classic white-collar future for me—as almost all immigrants love to imagine. Their reaction to me farming was to be bewildered. They could not understand why I would want to work so hard for little money. It also reminded them of the collective farms of the Soviet Union and everything associated with that. It took many conversations to convince them that owning a farm is owning a small business—the American Dream!—and that I am indeed putting my very expensive liberal arts education to good use as a female small business owner.”

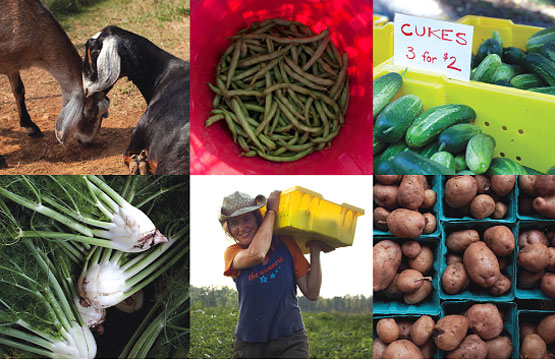

The couple is now in their eighth growing season at Stoney Lonesome, a 70-member, four-acre CSA farm.

Elliott also shares his farming knowledge at the Local Food Project (LFP), which he directs at the Airlie Center, a nearby conference center dedicated to environmental education and policy. In addition to providing food for the center’s kitchen, the LFP offers conferences, workshops, and other gatherings that offer education on organic gardening and farming to local food enthusiasts and prospective farmers. Elliott provides hands-on training in the center’s four-acre organic demonstration garden. In August, he organized LFP’s annual conference—this year titled “The Role of Institutions in the Future of Local Food.” Participants examined the ways in which institutions might advance regional food systems—from purchasing local food for cafeterias to creating educational farm and garden projects on institutional lands.

To assist on his many projects, Elliott hires interns who are curious, engaged, and smart. Most recently, they have been students from Oberlin and Colby colleges. Elliott attributes their interest in farming to “an idealism that often times accompanies a liberal arts education.”

As small-scale sustainable farmers, Elliott and Mandelheim Elliott are among a seemingly growing number of liberal arts graduates, including those from Vassar, who are making farming a way of life. As such, they are participants in the food movement that has emerged over the past decade or so, a global effort focused on developing more locally based, sustainable food systems as a way to enrich the economic, environmental, and social life of a particular community. Its growers are often young people with humanities majors and no formal agricultural training. (Their youth stands in stark contrast to the national trend of aging farmers—the largest group is 65 and older, according to the last Census of Agriculture in 2007.) They are alums like Todd Horner ’07 and Miriam Latzer ’97, who had never dreamed of driving a tractor or making their living as farmers, but are now creating niche markets for local organic produce by selling at farmers’ markets or starting CSA farms. Further, these graduates are invested in educating consumers about healthier eating and creating a healthier planet.

Why are so many young graduates interested in sustainable farming? Perhaps it is as Vassar Professor of Earth Science Jeff Walker suggests, “After over 100 years of being more and more removed from contact with the soil through mechanization, industrial farming, and supermarkets, people are discovering a fascination for the process of growing food and a desire to try their hand at it.” (Walker has felt the call himself. He and his wife, Kathy, have spent more than 14 years raising vegetables, goats, sheep, chickens, ducks, and turkeys on Singletree Farm, the 15-acre Hyde Park, New York, farm they run with their children.)

Mary Ann Cunningham, an assistant professor of geography who teaches the course “Food and Farming: From Local Food to Biofuels,” says these young farmers are “creating a new space that has been overlooked by mainstream agriculture. They are challenging the system.” What that comes down to, she adds, is a battle between small, independent farms and large agribusiness. Over the past 75 years, the number of farms in the United States has dwindled from its peak of 6.8 million down to about 2 million today. Not only are there fewer farms and farmers, but the population in the United States has grown from 127 million to 285 million. The increased demand for agricultural products has been met with the aid of large-scale mechanization, commercial fertilizers, and pesticides. Modern agriculture also requires more fossil fuel energy than we can rely on in the future, emits large amounts of greenhouse gases, and erodes nutrient-rich topsoil, critical for food production.

Many see small-scale sustainable farming as a more environmentally responsible means of food production, but independent farmers cannot compete with conventional commodity farms, which receive government subsidies to grow vast amounts of corn, wheat, and soy. Instead, independent farmers must rely on their creativity, problem-solving skills, and ability to articulate to consumers the pressing need for a new way to produce food and to educate them about the link between our food systems and the health of humans and the environment.

Walker, who teaches a course on soil and sustainable agriculture in Vassar’s Earth Science Department, says: “A student interested in farming should also be interested in history, biology, geology, chemistry, economics, political science, and anthropology. It is the quintessential multidisciplinary study if it is done right.”

Over 23 years of teaching at Vassar, Walker has seen the curriculum grow to accommodate an upsurge in interest in sustainable farming. “It felt pretty lonely when ‘Soils and Sustainable Agriculture’ was the only agricultural course in the Catalog,” he recalls. “Now it is in the company of some of the truly great courses in the curriculum taught by some of the best teachers. Vassar now offers a multidisciplinary view of agriculture from the science to the social aspects, the economic issues, and aesthetics, combined with the opportunity to do fruitful manual labor. It’s the best of all possible worlds.”

Todd Horner ’07, an English major at Vassar, has just completed his second growing season as the farmer at Nubanusit Neighborhood & Farm, a co-housing community in Peterborough, New Hampshire. He became interested in sustainable agriculture after taking an environmental studies course during his senior year at Vassar. He speaks passionately about the value of a liberal arts education and its relevance to farming. “Vassar helped me to make connections between seemingly disparate disciplines, which I think is what gave me the confidence to farm and certainly made farming seem pertinent to my other interests, like politics,” he says.

After graduation, he declined a position as a New York City Teaching Fellow, preferring instead to find a job that allowed him to exercise both body and mind. Following jobs working on trail crews and for a nonprofit land conservancy organization, he began to apprentice on farms. There was a maple syrup operation in the middle of New Hampshire, then an 80-member CSA with “an army of 14 interns,” and, finally, a raw milk dairy that also raised livestock for meat and produced vegetables and eggs. He started the CSA farm at Nubanusit in 2010, two years after the co-housing community was completed.

Nubanusit—situated on more than 70 acres of land with fields, woodlands, a pond, and nearly a mile of riverfront—is seen by residents as an attempt to face many of today’s social and environmental problems. Its smaller, clustered homes require less land, thus reducing the environmental impact of development and preserving more land for recreation, vegetation, and wildlife. A central power plant, fueled by wood pellets, heats and provides hot water for the entire community, and solar panels generate some of the residents’ electricity. Neighbors maintain a sense of community by sharing communal resources and gathering twice a week for meals and other activities in the Common House.

The farm produces an impressive array of vegetables and flowers for Nubanusit’s CSA and provides food for its 35 members. It relies heavily on the volunteer work of the co-housing residents—including Vassar grad Jim Heffron ’74—who contribute about 50 percent of the farm labor. As Horner puts it, “There are a lot of different formulas appearing. The family farm, which has a kind of iconic status in American mythology, is something to be celebrated and protected. To address the issues that have been coming up in agriculture, though, we’re going to need a whole portfolio of solutions. Nubanusit is one answer to the problem of producing food in a more sane way.”

He says, “I think people coming from a background in English or philosophy or history have a little catching up to do as far as the technical aspects of farming—chemistry or plant physiology, for example. But, some of the biggest challenges in farming aren’t technical—they’re social, they’re economic, they’re at the macro level.”

Horner points to an American culture that values intellectual occupations over those that are physical in nature, but he doesn’t believe there is a schism. “[In farming,] your plans change with the seasons, with the weather, with insects flying from thousands of miles away to suck the sap from your plants,” he says. “Never a dull day.” Figuring out how to respond to these challenges, he contends, provides opportunities not just for full-body engagement, but for creativity and critical thinking, too.

He recalls the days when he worked on a trail crew, thinning out two-foot wide ponderosa pines, or when he had to connect tractor attachments. “I really felt that I was exercising a whole different part of my brain. It felt a little bit uncomfortable at first, but one thing Vassar taught me was to find the value in being uncomfortable and to realize that that’s a really good place to be sometimes—that means you’re going to learn something.”

The new generation of growers includes many more women. According to the last Census of Agriculture in 2007, there has been a 30 percent increase in female farmers since 2002. Miriam Latzer ’97 is one example. Also an English major at Vassar, she got her first taste of farming during her Junior Year Abroad in New Zealand, where she spent long weekends on a sheep farm owned by a friend’s father, who taught literature at the University of Wellington. She would help out, “taking it all in,” an experience that offered only a glimpse of what it was like to be a farmer—she was not aware of the financial or managerial demands of the work. “These were the romantic days of flirting with farming,” says Latzer. The hard work would come later.

After graduating from Vassar, she worked on farms in Chile and New Zealand—this was the part one might describe as the “dating” stage of farming. Latzer says it was in Chile that she first worked hard at the vocation, spending six days a week for four months working in exchange for room and board. Later, she returned to New Zealand, where she worked on a deer farm.

Latzer made her way back to Poughkeepsie in 1999 and worked at the newly established Poughkeepsie Farm Project as an assistant grower and education coordinator though AmeriCorps. She gleaned as much as she could from the PFP’s head grower, Dan Gunther. “It wasn’t until I came back to Poughkeepsie that I actually learned enough to make managing a small farm seem even remotely possible,” she recalls.

After her experience at the PFP, she headed a bit farther north to Clinton Corners, New York, to work on the farm of a couple she met during her tenure at PFP, then partnered with another farmer to form her own business—Hearty Roots CSA in Tivoli, New York. Past the “flirting” and “dating” stages, this was more like moving in—or jumping in. She managed nine employees over a five-year period. “Hearty Roots gave me the opportunity to grow up as a human being, farmer, and community member,” she says. “It showed off my weaknesses and reminded me of my potential.”

Last summer, Latzer established Loose Caboose Farm, in Clermont, New York. The name was inspired by the two 8-by-20-foot caboose-like cabins on wheels that she, her boyfriend, Justin, and his daughter call home. The cabooses are “mated” to each other and attached to a trailer chassis. Latzer says that the farm’s name accurately conveys the “spirit of going-for-it” embodied in the project—and, clearly, in Latzer herself. “The caboose is ‘loose’ because there are no brakes,” she says.

She and her family relocated their moveable home to the 20-acre piece of property, where she grows a variety of vegetables, from bush beans to shallots to rare varieties of heirloom tomatoes. She sells her produce at a local farmers’ market on the Walkway over the Hudson. A former railway crossing that’s now a pedestrian bridge and state park, the Walkway spans the Hudson River connecting Poughkeepsie to Highland, New York. This particular market is meaningful to her. In a city with few supermarkets in its urban center and a high rate of poverty, the Walkway provides an opportunity for Latzer to serve a diverse spectrum of customers—from low-income local patrons who make purchases with WIC coupons to more affluent out-of-towners.

After working within the CSA model for the last few years, Latzer is trying her hand at a different style of farming at Loose Caboose, one that does not require an intense level of participation from community members or employees. Like many farmers (and Vassar alumnae/i), she likes to do things her way. Her vision includes teaching others how to preserve harvests by leading a series of workshops in which she provides fresh vegetables from the farm and hands-on instruction. Groups of participants will gather in each others’ homes or in the commercial kitchen that Latzer plans to build on the caboose for “put-ups,” or canning parties.

Now that she owns the land on which she farms, Latzer says, “It’s like I’ve married farming. I’ve made a deep commitment to spend the rest of my life trying to eke a living off the land.” Still, her fantasies about farming have been tempered by years of on-the-ground experience. There are personal challenges. “I have doubts about my abilities. A farmer has to be a plumber, electrician, and biologist,” she points out. “You also have to abandon a lot of fears—of spending money, for example. And you can’t control anything—the weather, the farm equipment, crop distributions.”

“The romance and poetry are gone,” Latzer admits. “What’s left is running a business.”

The business of farming can be a nail-biting experience, but as Pablo Elliott has seen, it can get better. “The first year we farmed, I completely freaked out, and then each year since, I have freaked out a little less,” he says. “We are just now getting a handle on what we’re doing.”

Each day Elliott tries to stay a few steps ahead of his farm crew and keep on top of a range of on-farm activities, and every day brings its own set of challenges. “Farming is a very humbling pursuit where what one person can do is limited. I came into this thinking, ‘I’m going to shovel my way to prosperity.’ It was a fantastic notion. Coming from a school like Vassar, one believes the sky has no limits. But farming does.”

He has spent enough time hoeing, crunching numbers, and making field plans that he has moved beyond his initial state of “irrational exuberance,” a condition he describes as common to new farmers. He now knows the concrete aspects of the business and the physical demands of CSA farming. Though he loves it, he still acknowledges that working a CSA is “a grind, with a 22-week harvest season.” It is for this reason that he concludes: “If I can pinpoint that most important ingredient in the survival of a new farmer, it is character.”

Valerie Linet ’98 has worked on various organic farms, most recently as head grower at Zen Mountain Monastery. She is a poet, writer, and social worker, currently working with families affected by HIV/AIDS. She lives in the Hudson Valley with her life partner and some hens.