Ruth Starr Rose: Illuminating African American Life in 1930-'40s Maryland

When people talk about the 20th-century American Scene artist Ruth Starr Rose (1887–1965), their eyes light up. By all accounts, she was born gifted, grew up fast, traveled far, and made the most unusual waves on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the 1930s and 1940s.

That’s where Rose focused her attention on a vibrant community of African Americans who did the work that fueled the Chesapeake Bay–area economy. The highly trained artist could easily have painted boats and waterfowl along the bay’s breathtaking shoreline; instead, she painted farmers, fishermen, oyster shuckers, cooks, gardeners, sail makers, housekeepers, and horse groomers. But scratch the surface and one will find another identity for these people; they are the descendants of enslaved African Americans who shaped Maryland and American history, including abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Underground Railroad “conductor” Harriet Tubman.

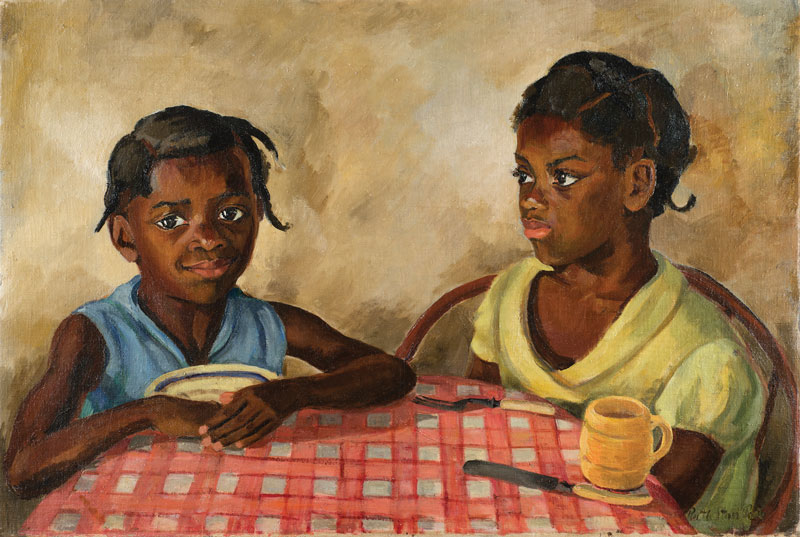

Over several decades, Rose produced hundreds of paintings, drawings, and lithographs that captured the dignity, beauty, faith, and optimism of African Americans in the segregated South at a time when racial stereotype and caricature were the norm.

Many of these works are on view through April 3 at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, a Baltimore institution specializing in the history of African Americans in Maryland. Beginning April 29, the exhibition will travel to the Armory in Easton, MD.

Rose was a white woman of great wealth and superior education. Both she and her mother, Ida May Hill, studied at Vassar. Rose graduated from the college in 1910, but her mother, who attended in the 1870s, left early and headed for Germany, where she studied piano with noted composer and performer Clara Schumann.

Among Maryland’s “high society,” Rose’s choice of subjects elicited shock and confusion. But Rose had a plan: She was determined to document the work life, family life, and spirituality of the people closest to her—her African American friends and neighbors—and to show that blacks and whites could and did get along.

Rose knew the people she painted because their lives had been connected for decades. In 1903, her parents moved the family from Wisconsin to Maryland’s Eastern Shore, into a sprawling brick domicile known as Hope House. It had been built in 1780 on nearly 300 acres in Talbot County’s prime tobacco territory. Photographs from the early 1900s through the 1930s show the Rose family and their black neighbors in nearby Copperville, MD, fishing, boating, and relaxing toget-her. Live concerts were regular affairs, and the audiences were integrated. Rose and her home also were magnets for a host of artists, intellectuals, and activists. Among them were African American tenor and composer Roland Hayes and author DuBose Heyward, best known for his novel Porgy, later adapted for the stage.

The Baltimore exhibition, on view since October 2015, is the first comprehensive presentation of Rose’s work. A focal point for the more than 75 pieces is a work that has come to be known as “The Black Mona Lisa.” It is a 1930s portrait full of haunting autumnal colors. The piece is clear evidence of the artist’s skill with brushwork and composition. The exquisitely beautiful face belongs to Anna May Moaney, who served as head cook to Rose and her family. Framed by a window and sitting on her front porch, she is bathed in a soft, honey-colored light. It is a perfect study of serenity. With her huge, velvet-brown eyes; full, burgundy lips; and a soft curtain of hair over one ear, she also exudes a quiet, self-confident sensuality. Most captivating, however, is the comfort she exhibits. The subject and the painter were clearly at ease with each other.

Exhibition curator Barbara Paca, an art historian and highly sought-after landscape architect whose family’s presence on the Eastern Shore goes back centuries, has been collecting Rose’s art for about 12 years; she knows this painting well.

She first saw the Anna May Moaney portrait in a conservator’s studio in Maryland. “I took it to New York and was told, ‘This is a serious, serious painting, and a serious, serious artist.’ And I think that’s mainly because of an emotional bond that was created. Anna May Moaney, the sitter, is looking at Ruth, the artist, with total trust. There is mutual respect. She knows the person painting her isn’t going to compromise her, not show her as a minstrel but show her for what she is, and what they both were: strong, determined women.”

According to Paca, the bulk of Rose’s work has been unaccounted for over the last 80 years. Word went out that Paca was looking for the artist’s pieces, and she started getting “calls from every corner of the world.” She says she also heard from collectors who wondered how she could possibly “be interested in art done by a white woman who makes fun of black people” by making them “look like they’re dignified.”

Jeffrey Moaney is one of the many relatives of Anna May Moaney who are surprised by the amount of work Paca is finding and how she’s managing to get such wide exposure for it.

“I saw the Anna May Moaney piece for the very first time in Barbara’s house,” says Jeffrey Moaney, an interior designer and Maryland native. “It was one of a number of pieces by Ruth Rose, and they were all prominently displayed. I know Barbara comes from a founding family herself. [Among her forbears is William Paca, 1740–1799, who was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.] She could have easily put her relatives above her fireplace. Yet she had my ancestors in that space.

“I am proud, and I am touched,” he says. “None of our family even knew these paintings existed until last year.”

The Vassar College art collection has a single Ruth Starr Rose work, a poignant gouache-and-ink drawing called Negro Head. It was a gift from the artist. Patricia Phagan, the Philip and Lynn Straus Curator of Prints and Drawings at Vassar’s Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, says Rose went on to enroll at the Art Students League of New York when she finished her Vassar studies. It was a wise move, Phagan says.

“That was the place to study, particularly for people who were interested in using art to capture the rhythm of everyday American life, and that was clearly the case with Ruth Starr Rose,” she says.

“I see her as a recorder of life, a documentarian, part of a national art movement in the ’30s and ’40s called the American Scene. She fits quite nicely in that aesthetic,” says Phagan.

Vassar records reveal that Rose studied with artist and printmaker Victoria Hutson Huntley (1900–1971), who would become a frequent visitor to Hope House, and lithographer George C. Miller (1894–1965). “He was one of the country’s leading authorities on printmaking,” says Paca. “She was learning at the master’s feet.”

Rose’s Baltimore show shimmers with works that are remarkable for the intense emotion they spark, the captivating stories they tell, and for the rich colors and the sumptuous draping of the clothing the subjects wear. But, more than clothing, Rose’s subjects wear attitudes. That rings clear in The Twilight Quartet, a large-scale oil she painted in 1936, showing members of the Moaney Quartet in tailored jackets of red, blue, and green, with billowing trousers and wide ties; it stirs images of Hollywood musicals and Harlem night clubs. That piece hung in Howard University’s Cramton Auditorium for decades, after having been featured in a 1937 New York Times article, which noted the piece had won the Mary Hills Goodwin Prize of $200 for its “fine brushwork, attention to detail, and expressive character.”

Howard University’s world-renowned art department was one of the first institutions to champion Rose’s work. In April of 1956, the university invited Rose to mount a solo exhibition there. It was to feature her collection of illustrations for Negro spirituals, the very music she was hearing in the African American church she and her mother attended. The invitation came from James A. Porter, the artist-scholar touted as the “father of African American art history,” who taught at Howard for more than 40 years and served as head of its art department and art gallery. In the exhibition brochure, he wrote: “Ruth Starr Rose’s visual interpretation of Negro spirituals is the most comprehensive, and probably the most sympathetic work yet to appear in the United States.” Howard professor, philosopher, historian, and author Alain Locke chose two of her spiritual illustrations for his 1940 work The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art.

Many of the same spiritual illustrations from that Howard exhibition decades ago can now be seen in the Maryland show. But Paca has plans to take them to an even wider audience in the form of a lavishly illustrated book. It’s a project that Rose herself started in 1941, but, due to prohibitive printing costs, the book was never printed.

According to Paca, Rose spent years in church services, listening to spirituals and asking the singers to tell her “exactly what they meant when they were singing ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ or ‘This Train is Bound for Glory.’ And the meanings, of course, were always deeper and heavier than the words suggested. That’s one reason Rose knew she needed someone with deep knowledge of music, history, and oppression to write the introduction to this book.” She settled on someone who spent a great deal of time talking politics and race at her waterfront home—the vocalist, actor, and activist Paul Robeson.

Baltimore philanthropists Sylvia and Eddie Brown, Paca, and a team of writers, musicologists, and book designers have recreated Rose and Robeson’s book of spirituals. Following Rose’s template, they have skillfully arranged the images, musical scores, and the lyrics as the congregation sang them, along with notes regarding their meaning, to create a timeless visual document of the origin of African American spirituals. When this book is published, Rose’s work—along with Robeson’s words—will receive even more of the attention it deserves.

LaFleur Paysour ’72 is an essayist, critic, and director of media relations for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. She was an English major at Vassar and published her first short story during her freshman year. As a student, she also served as a hostess and tour guide at Vassar’s Taylor Art Gallery.