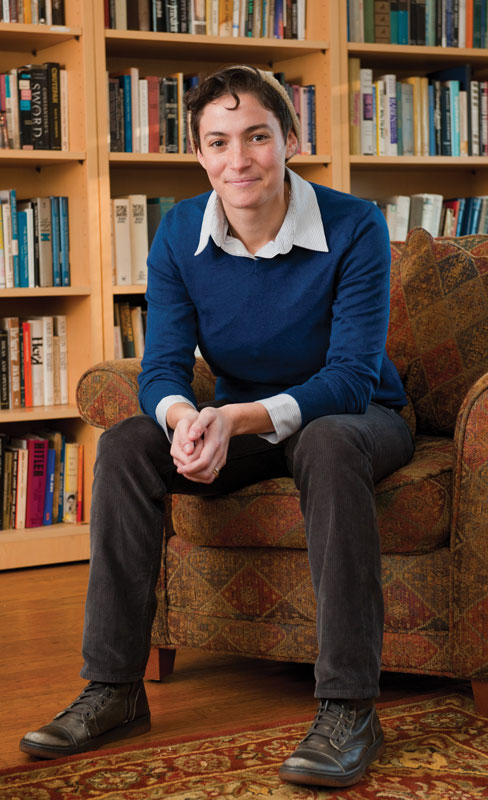

Finding Peace: Rabbi Kerry Chaplin

Rabbi Kerry Chaplin, the new Rose and Irving Rachlin Director for Jewish Student Life at Vassar, wants students to find just the right balance for growth. Her advice? Take constructive risks. Seek equilibrium. Return to the wisdom within the tradition.

As the new full-time director for Jewish student life at Vassar, Chaplin is responsible for the religious, spiritual, and cultural leadership of Jewish student life at the college.

The rhythm of Jewish life on campus is vibrant and varied. On Fridays, students not only cook well-attended Shabbat dinners (more than 100 students attended the first dinner of the fall semester) but they also lead Shabbat services at the Bayit, the college’s Jewish student cultural center. Typically, “The shaliach tzibbor, or prayer leader, will lead a discussion relevant to the week’s Torah reading or, more broadly, to the deep questions of life,” says Chaplin. During the fall semester, just after the attacks in France and Lebanon, one student leader asked the group to draw on the wisdom of children in order to understand how we might respond to these tragedies.

Students put their own spin on holiday rituals, too. For the festival of Sukkot last September, they constructed a sukkah (a temporary hut used for meals) in the center of campus, and led a “Pizza in the Hut” program in which they explored, among other topics, the laws of Sukkot from an LGBTQ perspective.

Over Hanukkah, students lit candles in a different campus location each night. On the fifth night, Chaplin says, students competed in a “very serious” dreidel tournament and fried (and ate) hundreds of latkes.

“You could smell the fried onions and potatoes all the way to North Gate!” she recalls.

During the spring semester, students tried their hand at decorating mezuzahs (small boxes containing Torah verses); they later hung them on their dorm and apartment doorposts.

But the students’ Jewish experiences don’t stop at Main Gate. Students joined and led part of a Tashlich service just after Rosh Hashanah in partnership with Vassar Temple, and several students have participated in services at Temple Beth El for Hoshanah Rabbah (the culmination of Sukkot) and regular Shabbat services. Students also take turns writing a monthly column for the Hudson Valley–based newspaper the Voice.

“They want to be a part of the local Jewish community,” says Chaplin. “And they want the community to see the fullness of Jewish life at Vassar from our diverse student perspectives.”

Their opinions are diverse, too. For example, despite what is widely perceived, Chaplin says, Vassar’s Jewish students have a breadth of attitudes toward Israel and Palestine. And even when they disagree, she says, they come together “because they choose to live together in pluralism.”

Chaplin, who also serves as assistant director for Religious and Spiritual Life, earned her BA in religious studies (with a minor in Hebrew) and an MA in nonprofit management from Washington University in St. Louis, before applying to rabbinical school. She went on to receive an MA in rabbinic studies and rabbinic ordination from the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles, CA. Before coming to Vassar in August 2015, she had served as rabbinic intern for the Hillel at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Chaplin’s approach to programming is to “ask students to take a constructive risk. For some students, that means delving into Jewish textual traditions in a way they never have before. For others that means living a vision of radically inclusive and pluralistic Judaism.”

Participating in workshops and discussions moderated by Resetting the Table, a national initiative of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, is one example of the latter. Its goal is to build the “capacity of American Jews to talk, study, and deliberate together on Israel across differences in background and views” without advocating a particular political viewpoint. Chaplin says Vassar students from a variety of backgrounds and relationships with Israel and Palestine have participated in the forums and they intend to continue the discussions going forward.

As students face academic, social, and other personal challenges, Chaplin’s pastoral priority is guided by an axiom she learned from a former student: there’s no growth in the comfort zone and no comfort in the growth zone. She helps students seek that “zone”—the point of equilibrium where they are grounded enough to recognize, accept, and use as an opportunity for growth the discomfort that inevitably presents itself in a rigorous academic and diverse social environment. She notes that this point of equilibrium is different for each student.

In addition to her work with students, Chaplin has done quite a bit of interfaith and conflict resolution work—much of it centered on Muslim-Jewish relations. Along with others in Vassar’s Office of Religious and Spiritual Life, she helped organize “A Conversation on Israel/Palestine with Imam Abdullah Antepli and Professor Yehezkel Landau,” held in November 2015 as part of the college’s “Dialogue and Engagement across Difference” initiative. Landau, from the Hartford Seminary, and Antepli, from Duke Divinity School, modeled a thoughtful and respectful dialogue on Israel/Palestine from their very different religious and personal perspectives.

While a student in rabbinical school, Chaplin served as a fellow at NewGround, a Muslim-Jewish partnership for change in Los Angeles. There, she helped to organize “Two Faiths One Prayer,” a project that brought together 20 Jews and Muslims in five different public places around Los Angeles to pray side-by-side in May 2015. At one location, more than 60 others joined in. Chaplin says the organizers wanted to “plant a seed of peace.” Chaplin describes the public prayer event as “an opportunity to share publicly the possibility of relationship across different identities and ideas—even and especially in our moments of greatest vulnerability, in prayer.”

There is wisdom in the world’s religious traditions, she says, adding that that, in part, explains why Judaism, a “minority” religion, has survived for so long. “The wisdom of Judaism is both perennial and flexible, continuing to change and grow with us,” she says.