History, Memory, and Legacies of the Holocaust

Poughkeepsie didn't seem all that far from Potsdam, Germany, last fall when Vassar students were chosen to participate in the newly designed seminar "History, Memory, and Legacies of the Holocaust." This multidisciplinary course—cocreated and cotaught by Maria Höhn from the history department, Silke von der Emde from German studies, and Debra Zeifman from psychology—explored the similarities and differences between how Americans and Germans commemorate and think about the Holocaust.

A wall of photographs in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC

“By studying the memorialization of the Holocaust from different disciplinary perspectives, students become aware of the fact that memory is never objective or neutral, and that the memory of the Holocaust has been transformed dramatically since 1945 in both Germany and the United States,” said Höhn. “Students also have a chance to rethink preconceived notions of ‘the Germans’ and ‘the Americans’ and come to a deeper understanding of the significance of Holocaust memory in Germany and in their own country.”

Since 2002, and following the founding of the Jewish studies program in 2000,Vassar has offered a Holocaust course, and various departments across the curriculum, from English to sociology, have designed their own courses that deal with aspects of the Holocaust or related questions, such as genocide, ethics, totalitarianism, and German history. With this seminar, however, Höhn, von derEmde, and Zeifman hoped to overcome existing disciplinary boundaries by synthesizing the more archival work of historians and the more speculative investigations of philosophers, literary critics, and psychoanalysis within Holocaust studies. “This approach empowered the students because they were able to bring their own disciplinary expertise to the class and understand how different disciplines approach this difficult topic,” said von der Emde.

To enroll in the course, students were required to submit short, personal statements. “The statements demonstrated that the students came to this course with academic questions, but also with very deep personal needs,” said Höhn. “For example, a Jewish student who had studied abroad in Australia and met German students there felt she couldn’t talk about the Holocaust with them. She was looking for away to help her learn how to talk about it with Germans her own age.”

“These third-generation students are very much aware that this is a passing of the guard, and they are coming to understand how much the past is part of the present in this country,” Höhn said. “A new time needs a new mediation. With no more immediate experience—no more liberator versus perpetrator—how do we mediate an experience like the Holocaust?”

Because “one of the key issues for us was to have a cross-cultural dialogue,” according to von derEmde, she and Höhn contacted the Moses Mendelssohn Center for European Jewish Studies at the University of Potsdam in Berlin to investigate whether German faculty and students would be interested in such a course. Julius Schoeps, director of the Mendelssohn Center and one of Europe’s leading scholars of Jewish history, was excited about the Vassar proposal and agreed enthusiastically to an exchange between Vassar and the Center. He commented, “In this exchange, students learn how the others are thinking.”

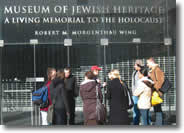

The first half of the course saw both the Vassar and the University of Potsdam students reading the same historical and theoretical works and sharing their ideas with one another through video conferencing, email, and Vassar’s own MOO technology (an interactive, online discussion space developed by Vassar faculty); the second half took Vassar students to Berlin in October and brought the German students to Vassar, New York City, Yale, and Washington, DC, in November.

“The highlight of the experience was the dialogue with our German colleagues,” said Laura Robbins ’06. “As an American Jew, the process of uncovering my own stereotypes about German culture and building friendships with German students despite our painful histories was an unparalleled experience for me.”

Irene Diekmann, who cotaught the course on the Potsdam end, added, “The amazing dynamic that developed as a result of the hard work between American and German participants helped students gain entirely new insights and experiences. And we as instructors received a wealth of new impulses for our own work.”

Höhn, von der Emde, and Zeifman plan to continue the course and exchange program in future years. And the Checkpoint Charlie Foundation in Berlin—which, along with the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Ministry of the Interior in Germany, and two Vassar alumnae, funded the course this year—was so impressed with the results that they have already indicated interest in future funding. All three professors agreed: with a course like this, Vassar can set the standard for some of the finest liberal arts learning in the 21st century.